Dal sito SANTI E BEATI:

San Giovanni Fisher, Vescovo e martire

22 giugno - Memoria Facoltativa

Beverley, Yorkshire (Gran Bretagna), ca. 1469 - Torre di Londra, 22 giugno 1535

Fu insigne apologista e pastore.

Giovanni Fisher e Tommaso More furono eminenti personalità della Chiesa e della società inglese, al tempo in cui Enrico VIII dopo il divorzio aveva iniziato il processo di separazione dalla Chiesa di Roma. Morirono martiri testimoniando insieme l'indissolubilità del matrimonio e l'unità della Chiesa. (Mess. Rom.)

Etimologia: Giovanni = il Signore è benefico, dono del Signore, dall'ebraico

Emblema: Bastone pastorale, Palma

Martirologio Romano: Santi Giovanni Fisher, vescovo, e Tommaso More, martiri, che, essendosi opposti al re Enrico VIII nella controversia sul suo divorzio e sul primato del Romano Pontefice, furono rinchiusi nella Torre di Londra in Inghilterra. Giovanni Fisher, vescovo di Rochester, uomo insigne per cultura e dignità di vita, in questo giorno fu decapitato per ordine del re stesso davanti al carcere; Tommaso More, padre di famiglia di vita integerrima e gran cancelliere, per la sua fedeltà alla Chiesa cattolica il 6 luglio si unì nel martirio al venerabile presule.

Martirologio tradizionale (22 giugno): A Londra, in Inghilterra, san Giovanni Fisher, Vescovo di Rochester e Cardinale, che per la fede cattolica e il primato del Romano Pontefice, per ordine del Re Enrico ottavo, fu decapitato.

Lo svegliano in cella: "Sono le 5. Alle 10 sarai decapitato". Risponde: "Bene, posso dormire ancora un paio d’ore". Questo è Giovanni Fisher, vescovo di Rochester, nella Torre di Londra, estate del 1535. Un maestro di coraggio elegante (come il suo amico Tommaso Moro, già Gran cancelliere del regno, anche lui nella Torre aspettando la scure). Figlio di un orefice, Giovanni è stato a Cambridge come studente e poi come promotore del suo sviluppo, aiutato da Margherita di Beaufort, nonna di Enrico VIII. Sacerdote nel 1491, nel 1514 lascia Cambridge perché nominato vescovo di Rochester, e si dedica solo alla diocesi. Ma la rivoluzione luterana, con i suoi riflessi inglesi, lo porta in prima fila tra i difensori della Chiesa di Roma, con i sermoni dottrinali e con i libri, tra cui il De veritate corporis et sanguinis Christi in Eucharistia, del 1522, ammirato in tutta Europa per la splendida forma latina. E fin qui egli si trova accanto a re Enrico, amante della cultura e “difensore della fede”.

Il conflitto scoppia con il divorzio del re da Caterina d’Aragona per sposare Anna Bolena. E si fa irreparabile con l’Atto di Supremazia del 1534, che impone sottomissione completa del clero alla corona. Giovanni Fisher dice no al divorzio e no alla sottomissione, dopo aver visto fallire una sua proposta conciliante: giurare fedeltà al re "fin dove lo consenta la legge di Cristo". Poi un’altra legge, l’Atto dei Tradimenti, è approvata da un Parlamento intimidito, che ha tentato invano di attenuarla: così, chi rifiuta i riconoscimenti e le sottomissioni, è traditore del re, e va messo a morte.

Nella primavera 1534 viene portato alla Torre di Londra Tommaso Moro, e poco dopo lo segue Giovanni Fisher. Sanno che cosa li aspetta. E il papa Paolo III immediatamente nomina Fisher cardinale-prete del titolo di San Vitale nel concistoro del 21 maggio 1535, sperando così di salvarlo: e invece peggiora tutto. Re Enrico infatti dice: "Io farò in modo che non abbia più la testa per metterci sopra quel cappello". Come previsto, i processi per entrambi, distinti, finiscono con la condanna a morte. Ma loro due, da cella a cella e senza potersi vedere, vivono sereni l’antica amicizia e si scambiano lettere e doni: un mezzo dolce, dell’insalata verde, del vino francese, un piatto di gelatina... Sono regali di un loro amico italiano, Antonio Bonvini, commerciante in Londra e umanista.

Alle 10 del 22 giugno 1535, Giovanni Fisher va al patibolo. Per tre volte gli promettono la salvezza se accetta l’Atto di Supremazia. Lui risponde con tre affabili no, e muore sotto la scure. La sua testa viene esposta in pubblico all’ingresso del Ponte sul Tamigi. Quindici giorni dopo uno dei carnefici la butterà nel fiume, per fare posto alla testa di Tommaso Moro. Il suo corpo nudo rimase esposto per tutto il giorno sul patibolo e venne seppellito senza cerimonie in una tomba anonima del cimitero di Ognissanti: in seguito venne traslato nella cappella di San Pietro in Vincoli nella Torre.

Fu beatificato da Leone XIII, insieme ad altri 54 martiri inglesi, il 29 dicembre 1886.

Il 19 maggio 1935, in Roma, papa Pio XI lo proclamerà santo insieme a Tommaso Moro. E sempre insieme li ricorda la Chiesa.

Curiosamente il suo culto è vivo anche presso la comunità anglicana che però fissa per la celebrazione della sua memoria la data del 6 luglio.

Autore: Domenico Agasso

User Tag List

Risultati da 1 a 10 di 32

-

21-06-07, 22:22 #1**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

22 giugno - S. Giovanni Fisher, vescovo e cardinale, martire

22 giugno - S. Giovanni Fisher, vescovo e cardinale, martire

-

21-06-07, 22:28 #2**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

June 23

Excerpts from the Book

BY MICHAEL DAVIES

The Neumann Press [$20.95]

Published on the Web with permission of the author.

NOTE: All the illustrations in the above book are in black and white;

the bust of the Martyr was found in another work [art] and set onto a scenic,

as were the other color images we have used for this presentation.

The artisan, TORRIGIANO also crafted a statue of Lady Margaret Beaufort,

John Fisher's patron, a photograph of which is in the Davies book.

Part 1: Early Years

Part 2: The See of Rochester

Part 3: Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon

Part 4: Lutheranism Refuted

Part 5: The English Reformation

Part 6: A Zealous Pastor

Part 7: Anne Boleyn

Part 8: Cardinal Wolsey

Part 9: The Troubled Conscience of the King

Part 10: Pressure on the Pope

Part 11: Defender of the Queen

Part 12: The Downfall of Wolsey and the Battle in Parliament

Part 13: Capitulation and Submission of the Clergy

Part 14: Thomas Cranmer

Part 15: The Nun of Kent

Part 16: Oath of Succession and the Refusal

Part 17: The Tower of London and the Act of Supremacy

Part 18: The Carthusian Martyrs

Part 19: Imprisonment in the Tower

Part 20: The Trial of John Fisher

Part 21: John Fisher's Martyrdom

Part 22: The Henrican Schism

Part 23: Canonization

FONTE

-

21-06-07, 22:30 #3**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

Excerpts, Part 1: Early Years

In 1469, the exact date is not known, a son was born to Robert, a prosperous mercer (dealer in textile fabrics), and Agnes Fisher who lived in Beverley in the East Riding of Yorkshire, in the heart of the plain which stretches eastward to the broad waters of the Humber. The town was dominated then, as it is today, by its minster, the collegiate church of St. John of Beverley. It was, at that time, one of the most prosperous cloth-making and marketing towns in England, and famous for its mystery plays. Robert and Agnes named their son John. He had been born during one of the most tumultuous periods of the Wars of the Roses between the houses of York and Lancaster. "The life of Fisher began amidst the horrors of civil war, and ended amid the horrors, far greater to a soul like his, of religious rebellion and impiety." 1 In 1471, two years after John's birth, the saintly Lancastrian king, Henry VI, who had been deposed and then restored, was murdered in the Tower of London and replaced by the Yorkist king, Edward IV: Edward died in 1483 and the throne was eventually seized by his brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester (Richard III), after he had disposed of those with a better claim, including his brother's two sons, the thirteen year old Edward V and his younger brother Richard, Duke of York (the princes in the Tower). The Lancastrians gave their support to Henry Tudor, a Welsh nobleman who had a somewhat dubious claim to the throne through his mother, the remarkable Lady Margaret Beaufort, who was to become the patron of John Fisher. Henry fled to Brittany to avoid being murdered by King Richard's agents. He landed at Milford Haven in Wales in 1485, marched into England and defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth. Richard was killed by Rhys ap Thomas, a Welsh gentleman who was knighted by the new king, now Henry VII, in recognition of this service. The accession ot Henry VII brought the disastrous Wars of the Roses to an end and gave the country a much needed period of firm government and stability.

Robert Fisher died in 1477 when John was only eight years old, leaving his widow financially well off. Four children were mentioned in his will, but the only two of whom anything is known are John and his brother Robert, who became his steward at Rochester. There was at least one sister who married a man named Edward White, but not even her name is known. Agnes Fisher remarried, and her new husband, Thomas White, a merchant, treated John as his own son and gave him the best education Beverley could provide. Four children were born of Agnes' second marriage. There were three boys, two of whom, John and Thomas, became merchants, and the third, Richard, became a priest The daughter, named Elizabeth, became a Dominican nun. It was for this half sister that, while a prisoner in the Tower of London, John wrote A Spiritual Consolation and The Ways to Perfect Religion. Elizabeth refused to take the Oath of Supremacy in the reign of Elizabeth, and went to live out the remainder of her life in a poor monastery on what was then the Island of Zeeland in the Netherlands. Of her life there and her death nothing is known.

A BRILLIANT SCHOLAR

The young John Fisher proved himself so brilliant a pupil at the local grammar school attached to the minster that in 1483 he went up to Cambridge at the age of fourteen. This was the year when Richard III seized the throne. John was a tall, lanky lad who, as a man, was over six feet in height "exceeding the common and middle sort of men". His forehead was smooth and large, his nose of a good and even proportion. His hair was auburn, his eyes were grey, and his face was serious. His habitual expression in later life was described as one of "reverend gravity". John was devoted to scholarship, but his later writings show that his interests extended well beyond book learning. His sermons and writings show that he had a deep love of the English countryside. Hunting was one of the rare relaxations that he permitted himself as a bishop while his health allowed.

When he was a prisoner in the Tower, after years at the University, in the household of the greatest lady in the land, as bishop and member of the King's Council, none of these experiences seem tohave made so deep an impression on his mind as the sight of a blackthorn blossoming in May, of parched grass springing green again with the first heavy shower, of a huntsman treading the fallows, running over hedges and creeping through thick bushes while he calls all the day long upon his dogs. To the end of his life, John Fisher was a countryman as well as a scholar. 2

John liked to spend his day in the company of Our Lady. He would say: "Therefore let us go into this mild morning, our Blessed Lady Virgin Mary."

His career in the University was all that the most optimistic of his grammar school masters could have hoped. His college was Michael House (later incorporated with Trinity College). He obtained his degrees in the least possible time and with great distinction. He received his BA in 1487; in 1491 he became a Master of Arts, a Fellow of Michael House, and was ordained to the priesthood at York on 17 December at the age of twenty-two. A papal dispensation had been necessary for his ordination while under the canonical age. 3

In 1501 he received the degree of Doctor of Divinity and was elected Vice-Chancellor of the University, after having been elected Master of Michael House and Proctor. In 1504 he was elected Chancellor of the University, and was re-elected annually until 1514 when he received the unique distinction of being elected Chancellor for life. Cambridge owes him an immense debt for those years of service.

In 1494 John Fisher went to London with a colleague to obtain influential support for the university in a dispute with the town. The most important aspect of these negotiations was that they made it necessary for him to visit the court at Greenwich which brought him to the attention of Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby. The Proctor's book still contains the note of the expenses for the journey in his own handwriting: "For the hire of two horses for 11 days, 7 shillings; for breakfast before passing to Greenwich, 3 pence; boat hire, 4 pence. I dined with the lady, mother of the king."

LADY MARGARET BEAUFORT

Lady Margaret was the mother of King Henry VII, who had a great respect for her. She had a deep devotion to the Church and a great love of learning. She was a patron of the relatively new printing press. Caxton had produced the first book printed in England when John Fisher was eight years old. She very soon came to appreciate the exceptional worth of the young priest, and asked him to be her confessor. He was able to say in all sincerity in a letter written in 15Z7: "Though she chose me as her director to hear her confessions and to guide her life, yet I gladly confess that I learned more from her great virtue than ever I could teach her." Under his guidance Lady Margaret was to do a great deal for religion and scholarship. The depth of her religious devotion can be gauged from Fisher's reference to it in his oration for her Month's Mind: 4

In prayer every day at her uprising, which commonly was not long after five of the clock, she began certain devotions, and after them, with one of her gentlewomen, the matins of Our Lady, then she came into her closet, where, with her chaplain, she said also matins of the day, and after that daily heard four masses on her knees, so continuing in prayer until the hour of dinner, which on the eating day was ten o'clock, and on the fasting day eleven.

After dinner full truly she would go to her stations to three altars daily, and daily her dirges and commendations she would say, and her Evensong before supper; both of the days of Our Lady, besides many other prayers and psalters of David through the year, and at night before she went to bed she failed not to resort unto her chapel, and a large quarter of an hour to engage in her devotions. No marvel all this long time her kneeling was to her painful, that many times it caused in her back pain and disease, nonetheless when she was in health she failed not to say the Crown of Our Lady, which containeth sixty and three Aves, and at every Ave a kneeling, and as for meditation she had divers books in French wherewith she occupied herself when weary in prayer, wherefore divers she did translate into English.

1. T.E. Bridgett, Life of John Fisher (London, 1888), p.5.

2. R.L. Smith, Saint John Fisher (London, 1954), p.1.

3. The entry in Archbishop Rotherham's Register reads: 17 Dec. 1491

Presbiteri. Mr. Joh. Fysher artium M. Socius domus sive hospicii Sancti Michaelis Cantibrig. ad titulum societas (sic) sue.

4. Month's Mind: The Requiem Mass celebrated on the 30th day after death.

-

21-06-07, 22:32 #4**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

Excerpts, Part 2: The See of Rochester

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY

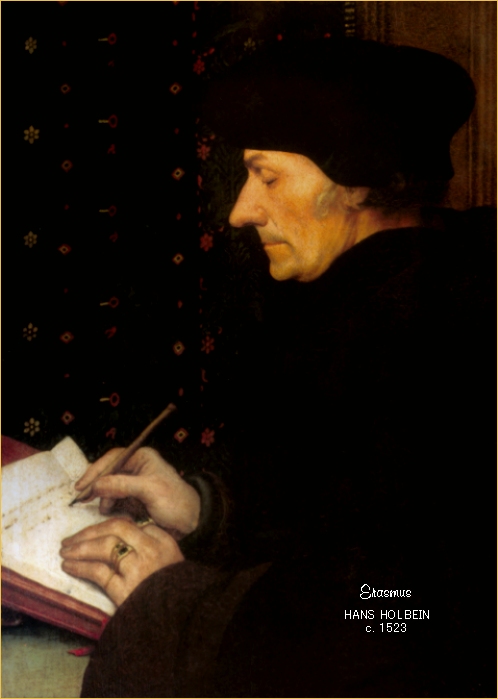

Compared with the university life of Oxford at the beginning of the sixteenth century, Cambridge was neglected and almost a backwater. But John Fisher influenced royal patronage to establish Christ's College, to implement the revenues of Queen's College, and of King's College, and to found St John's. He used the opportunity of framing their statutes to quicken the pace and change the direction of scholarship in Cambridge. He considerably enhanced the prestige of the University by persuading Erasmus to teach Greek there.

Erasmus admired the holiness of John Fisher's life, and there can have been few men that he respected more. In a letter to a priest in Rome in 1512 he wrote: "Unless I am sadly mistaken, he is the one man at this time who is incomparable for uprightness of life, for learning, and for greatness of soul." In 1516 Erasmus published his Novum lnstrumentum. This was the Greek text of the New Testament with Erasmus's own translation into Latin. This work was the cause of Fisher deciding to learn Greek at the age of forty-eight, and he had the good fortune to receive his first instruction from Erasmus himself; who stayed with the bishop in Rochester for ten days in the same year. Fisher then went on to learn Hebrew. The fact that he was able to gain a good working knowledge of these languages despite his time-consuming duties as bishop, chancellor, and counsellor to the king provides a striking indication of his tenacity of purpose.

Fisher realized that the Church in England was in great need of more good preachers and better training for the clergy. Very few priests and few bishops possessed a solid grounding in theology, and the parish clergy could not pass on to their flocks what they themselves did not possess. It must be borne in mind that the seminary system was not instituted until after the Council of Trent (1545-1563). In 1502 Fisher obtained a papal bull giving Cambridge the privilege of appointing twelve preachers from the university, who were authorized to preach anywhere in the country: In 1503 Fisher persuaded his royal patron to endow Lady Margaret readerships in Divinity at both Oxford and Cambridge. In 1504 a preachership was established at Cambridge, the selected priest preaching sermons in London and in the churches of Lady Margaret's many manors. John Fisher undertook this work himself when time permitted until his episcopal consecration in November that year. Lady Margaret paid for the printing by Wynkyn de Worde 5 of a series of sermons that her confessor preached before her on the Penitential Psalms. 6 The book was reprinted frequently during the Saint's lifetime and is of particular interest as the first publication in which an English translation of the Scriptures was used.

John Fisher's service to Cambridge did not cease with his eventual appointment to the See of Rochester. And to its credit Cambridge was grateful:

The king and his courts might thunder against Bishop Fisher, they might confiscate his goods and confine his person to the Tower. But until they killed him, he remained Chancellor of the University. It was a rare example of courageous loyalty in an age of time-servers. 7

BISHOP OF ROCHESTER

When the see of Rochester became vacant in 1504 King Henry decided to appoint his mother's confessor as the new bishop. He described Fisher as a man of "great and singular virtue, as well in knowledge and natural wisdom, and especially for his good and virtuous living and conversation". The king confessed that in his days he had "promoted many a man unadvisedly and would now make some recompense to promote some good and virtuous men." The first of these was John Fisher, not the man who deserved best of him, but the man who deserved best of God. It was a novel criterion which surprised the courtiers who attributed the appointment solely to Lady Margaret's influence. They were wrong. The king had been personally impressed by the priest's profound spirituality which confirmed all that his mother had told him. He stated explicitly that his mother had played no direct role in his choice of Fisher:

Forsooth, indeed the modesty of the man together with my mother's silence speaks in his behalf. I protest she has never so much as opened her mouth to me on the subject; his pure devotion, perfect sanctity, and great learning, which I have myself often observed, and have heard others speak of, are his only advocates.

By a Bull dated 14 October, 1504, John Fisher was advanced to the see of Rochester and was consecrated on 24 November in the same year at the age of thirty-five. As a bishop he was a member of Convocation, of the House of Lords, and of the King's Council. He remained Chancellor of Cambridge University, and for the first years confessor to Lady Margaret. He carried out each of these duties with scrupulous care and unlike most bishops of his day he did not seek preferment in Church or State, nor did he build up numerous benefices to supplement his income, and staff them with poorly paid curates. The bishop had great compassion for the poor, and spoke of:

The labourer when he is at plough tilling his ground, and when he goes to his pastures to see his cattle, or when he is sitting at home by the fireside, or else when he lies in bed waking and cannot sleep. And the poor women also in their business, when they be spinning of their staffs or serving of their poultry.

The year 1509 was a significant one in the life of the Saint. Both Henry VII and his mother Lady Margaret died, and John Fisher, acknowledged as one of the greatest preachers of his day, preached the funeral sermon for the king and the sermon for her month's mind for his mother. Lady Margaret was buried in Westminster Abbey, and the gilt-bronze figure on her tomb is considered to be one of the greatest achievements of the Florentine sculptor Pietro Torrigiano. The epitaph was composed by Erasmus for which Fisher paid him twenty shillings. The iron screen was donated by the grateful St. John's College in 1529.

5. Wynkyn de Worde, who was born in Holland or Alsace, was a pupil of William Caxton. In 1491 he succeeded to his stock in trade in Westminster and in 1500 moved to Fleet Street He made great improvements in the quality of printing and typecutting, including the use of italic, and printed hundreds of books.

6. In the Vulgate, and Douai Bibles, the Penitential Psalms are 6, 31, 37, 50, 101, 129, and 142.

7. Smith, op. cit., p. 3.

-

21-06-07, 22:33 #5**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

Excerpts, Part 3: Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon

THE ACCESSION OF HENRY VIII

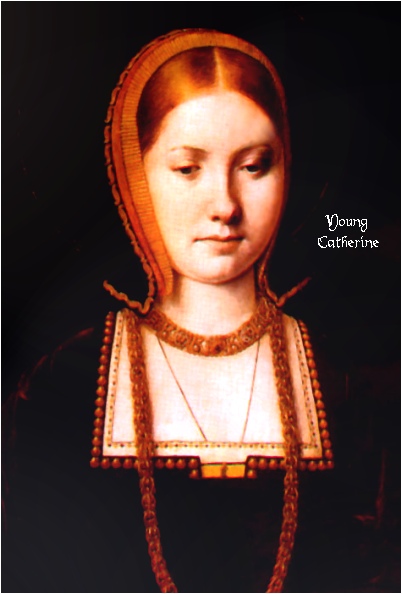

Henry VII was succeeded by his eighteen year old son Henry, who married Catherine of Aragon, the widow of his brother Arthur, on 11 June 1509, within two months of his accession to the throne. Catherine, the daughter of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, had come to England in 1501 at the age of sixteen to marry Arthur, Prince of Wales, the fifteen year old son of Henry VII. The wedding was solemnized in St Paul's Cathedral on 14 November. Arthur died on 2 April 1502, within five months of the marriage. King Ferdinand demanded the return of that part of the dowry he had already paid, 100,000 crowns, and on Catherine's behalf he claimed her promised marriage settlement, one third of the revenues of the earldoms of Wales, Cornwall, and Chester. Henry VII, very loath to lose either Catherine's dowry or the Spanish alliance, arranged for her to be engaged to Arthur's younger brother Henry, aged twelve. A papal dispensation from the first degree of affinity was necessary in order to make an eventual marriage possible, and this was issued by Pope Julius II in 1504. Within seven weeks of his accession to the throne in 1509, the eighteen year old Henry married the twenty-six year old Catherine. He did so of his own volition with no pressure being exerted upon him from any source whatsoever. Henry himself had assured the Spanish ambassador of his undiminished attachment to Catherine and of his ardent desire to marry her. Catherine made a solemn affirmation, confirmed by ladies of the Spanish court, that her marriage with Arthur had never been consummated, and that she came to Henry as a virgin-bride, a fact which was never denied by Henry in person. She was thus married as such, dressed in white and wearing her hair loose. The royal couple were married by the Archbishop of Canterbury in the oratory of the friary church just outside the walls of Greenwich Palace.

On Midsummer day a more public and splendid celebration of their union took place when Henry allowed his bride to share in his coronation at Westminster Abbey. On Saturday 23 June the traditional eve-of-coronation procession to Westminster was greeted by vast and enthusiastic crowds. The beautiful young queen was acclaimed as she passed by in a litter "borne on the backs of two white palfreys trapped in white cloth of gold, her person apparelled in white satin embroidered, her hair hanging down her back, of a very great length, beautiful and good to behold, and on her head a coronal, set with many rich stones." The Londoners, who had taken the Spanish queen to their hearts, cried out "God save you!" Their love for Catherine remained undiminished throughout her life, and even in the dark days of her repudiation by the king they would allow no one to replace her in their affections.

The royal couple passed through streets hung with tapestries and cloth of gold, and Henry seemed almost to outshine his bride with the riot of diamonds, rubies, and other precious stones that adorned his person. The coronation was followed by a banquet in Westminster Hall (where John Fisher and Thomas More would be condemned). It was greater than "any Cæsar had known", and opened with a procession bearing the dishes led by the Duke of Buckingham and the lord steward riding on horseback. The great rejoicing which followed the wedding and coronation occupied the court during much of the remainder of the year in an almost unbroken round of revels, pageants, tournaments, banqueting, dancing, and making music. Many new Knights of the Bath were created in honour of the coronation, including a certain Thomas Boleyn, who had married a member of the aristocratic Howard family, and was the father of one son and two pretty daughters, Mary and Anne. The dark days of the Wars of the Roses seemed to be no more than a fading memory. The mood of optimism which pervaded the country was expressed by Thomas More who, inspired by the joy of the coronation, wrote: "This day is the end of our slavery, the fount of our liberty; the end of sadness, the beginning of joy."

The eighteen year old king was initially very popular with his subjects. He was handsome and excelled in all the accomplishments most admired in a person of his station-in the martial arts, hunting, boxing, wrestling, tennis, archery, music, dancing. His standing armour which can still be seen in the Tower of London suggests that he was six feet two inches in height, a very tall man for those days (as was John Fisher). He was not only tall but powerfully built, with muscular arms and legs. It was his proficiency in the martial arts that gave the young king most satisfaction. For several years after his marriage the queen and her ladies, members of the court, and foreign ambassadors would be summoned to admire Henry fighting at barriers with the two-handed sword or the battle axe, or breaking lances in tournaments on horseback. The young king invariably emerged victorious and received the prize, due, he was sure, to his physical prowess and martial skills, but also, no doubt, to the prudence of his opponents who realized that defeating the king was not a wise thing to do.

Henry was an avid collector of musical instruments and could playagood number of them with thefIuencyofa professional musician, among them the gittarone, lute, cornet and virginal. He would take part in evening concerts for the court, alternating with professional musicians, and there was never any doubt who received the loudest and longest applause. Henry had a strong sure voice, could sight-read easily, and was an accomplished composer of both light and serious music, writing at least two five part Masses. He would later scour the country for men and boys to sing in the chapels royal, and even lured singers from Wolsey's choir of which he was said to be jealous. The king had a great interest in art and Holbein found at Henry's court the welcome and success that he had been denied in Germany. 8 The king delighted in speaking French, Latin, Italian, and Spanish to the ambassadors to his court He was an avid student of theology, the scriptures, and philosophy, and considered himself to be an exemplary Catholic and an outstanding defender of the Church. During the lavish masques and pageants which he loved, and organized at tremendous expense, the king would sometimes disappear to return incognito as a masked actor, musician, or dancer to receive tumultuous applause which would rise to a crescendo when his mask was removed to reveal the identity of the star performer (which was certainly known to most of those present during his whole performance). The incessant praise and adulation that the young king received inevitably led to vanity on his part, and to resentment of any criticism from anyone for any reason.

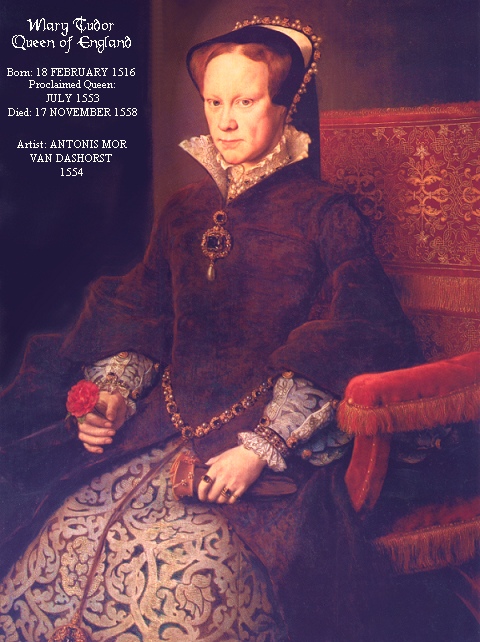

CATHERINE OF ARAGON----A SAINTLY QUEEN

The graceful person, invariable dignity, and impeccable virtue of Queen Catherine made her loved and admired throughout the kingdom. Her great misfortune was that of the five children she bore Henry, three sons and two daughters, only one daughter survived infancy, the Princess Mary who would eventually ascend the throne and restore the Catholic faith in England. Like her mother, and due in no small part to her mother's influence, Mary never once wavered in her fidelity to Rome and to the Mass. The princess was very well educated, had a great love of music, and was an accomplished linguist By the age of eleven she was already translating Thomas Aquinas out of Latin. Within ten years of the marriage Catherine had already lost her beauty, miscarriages had much to do with this, and the king was consoling himself with a series of mistresses.

8. There is no known painting of John Fisher by Holbein, but there are two beautiful sketches in red chalk by the great artist. One is in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle and the other in the British Museum.

-

21-06-07, 22:35 #6**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

Excerpts, Part 4: Lutheranism Refuted

The Diocese of Rochester, established by St. Augustine of Canterbury himself was the smallest in England, comprising of ninety-nine parishes, almost all in the western part of the county of Kent It was a very poor diocese, with an income of only £350 a year, and was generally considered to be no more than a stepping stone to advancement in the hierarchy; but John Fisher was content to remain there for thirty years uritil his Martyrdom in 1535. His brother Robert acted as his steward, and had strict instructions to ensure that the bishop's household should live within its income, and never incur debt. The cathedral-church and bishop's palace occupied half the space within the walls of the city. There were no more than 148 houses inside the walls. Rochester had been an ancient British and then Roman fortress which occupied a strategic position on the River Medway where the high road between London and Canterbury crosses it. 10 The little, walled town, dominated by the massive block of the castle on its hill, lay beside a bridge over the Medway directly in the path of all who travelled from London to the coast and vice versa. This had a considerable and unwelcome effect upon John Fisher's life as Bishop of Rochester. Many persons of note rode that way, ranging from royal embassies and foreign merchants to poor scholars. The bishop was constantly called away from his large library, one of the finest in Europe, to offer hospitality to visiting strangers.

DEFENDER OF THE FAITH

Many spoke to the Bishop of Rochester about the new ideas which were initiating a religious revolution upon the Continent, namely the heresy of Protestantism. Pope Julius II had decided to replace the existing St. Peter's Basilica with what would be the most magnificent church in the entire Christian world. To raise funds for this project the pope published an indulgence in Poland and Frante. His successor Leo X extended the indulgence to the northern provinces of Germany. The indulgence was preached by the Dominicans, in particular a friar named Tetzel, in a manner which gave the impression that sins could be forgiven or souls released from Purgatory simply by making a cash payment. Some Catholic apologists have claimed that criticisms of this indulgence and the manner in which it was preached have been exaggerated, but the facts are even more squalid than is generally realized. Father J. Lortz writes:

When the 25-year old Albert of Brandenburg, who already held two bishoprics and a convent, was elected Archbishop of Mainz, he desired to combine in his hand this archdiocese with the two dioceses he already held. This was what was called a cumulus, specifically forbidden by Church law. The ratification fees for the archepiscopal chair to be paid by Mainz to Rome amounted to 14,000 gold florins. The Roman Curia now offered Brandenburg to allow the desired cumulus for an additional payment of 10,000 gold florins. Albert, therefore, had to pay Rome, including the quite considerable gratuities, a sum of more than 25,000 gold florins. He borrowed the required amount from the banking house of Fugger. To enable him to repay this loan, the Roman Curia assigned to him for the lands of Mainz and Brandenbug the publication of the indulgence for the benefit of the rebuilding of St. Peter's in Rome. The terms provided that one-third of the receipts would go to the Curia, one-third to Albrecht, and one-third to the Fuggers. This was the occasion for the indulgence sermons of Tetzel which were soon to begin. They have gone down in history----weighted with the opprobium of the contemptible charlatan sales tactics used to offer so-called letters of indulgence for money, hardly different from selling merchandise. There is no doubt that Tetzel preached what amounted to the often-quoted popular jingle: "As soon as the coin clinks in the box, the soul leaps into Heaven." There is no doubt that the original bargain between the Curia and Albrecht, as well as the subsequent indulgence peddling, would have been condemnd by early Christianity as a grave case of simony.

It is not surprising that with such a Curia the care of souls, prayer, and the Sacraments did not carry very much weight, and that the oncoming Reformation was met with few religious weapons. 11

Luther responded to Tetzel by nailing his 95 theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg on 31st October 1517. His initial protest against what was an evident abuse of the doctrine of indulgences was far from unjustified, but he quickly progressed to a denial of the doctrine itself; then to a rejection of doctrines and practices such as the papal primacy, clerical celibacy, religious orders, pilgrimages, Masses for the dead, Communion under one kind, transubstantiation, the sacrifice of the Mass, and eventually affirmed that the only Sacraments instituted by Our Lord were Baptism and the Eucharist His fundamental heresy of Justification by Faith alone had been formulated in 1515, two years before nailing up his theses. [Emphasis in bold added.] In 1520 Luther formalized his heresies in three books the most important of which was The Babylonian Captivity of the Church (De Captivitate Babylonica Ecclesiæ) published in Latin and German. Henry VIII, who considered himself to be no mean theologian, found the principles ofLutheranism repugnant, and refuted them with his Defence of the Seven Sacraments (Assertio Septem Sacramentorum) 1521. The Dean of Windsor carried the book to Rome and in a full consistory presented it to Pope Leo X who, on 11 October of that year, bestowed upon Henry the title Defender of the Faith. 12 It has been suggested that the book was in reality written by Fisher, and it was included in his Latin Opera Omnia long after his death, but although he may have advised the king during its composition the Bishop denied emphatically that he was its author. In view of what was to transpire later in Henry's reign there is evident irony in the fact that three of his principal themes were his affirmation of the papal primacy, the condemnation of schism, and a defence of the indissolubility of marriage. Luther replied to Henry terming him, among other things, "a fool, an ass, a blasphemer, and a liar." Fisher came to the king's defence in 1525 with his book Defensio Regiæ Assertionis (A Defence of the Assertions of the King of England against Luthers "Babylonian Captivity"). Fisher's books refuting Lutheranism were written in Latin and placed him immediately among the leading theologians of Europe. He upheld Catholic teaching on the priesthood with his book Sacri Sacerdotii Defensio Contra Lutherum, 1525, and on the Real Presence and the Eucharistic Sacrifice in De Veritate Corporis et Sanguinis Christi in Eucharistia, against Oecolampadius, in 1527.

Fisher saw clearly that the teachings of the apostate friar were treason to the Faith and poison to the souls of simple men. 13 His duty as a bishop, and his inclination as an honest man, both impelled him to fight the spreading of such a plague. The books that he wrote in his library, the sermons he preached in his own diocese, in London at St. Paul's Cross, and in Cambridge, carried his challenge to Luther and his fellow Protestants, and made his name famous in continental Europe where he was soon recognized by Catholic scholars as the master theologian of England, even though he only set foot once outside the realm and rarely travelled further from home than to Cambridge, where he would watch the building of St. John's. A contemporary writer pays him this tribute:

He was also a very diligent preacher and the most notable in all this realm, both in his time or before or since, as well for his excellent learning as also for edifying audiences, and moving the affections of his hearers to cleave to God and goodness, to embrace virtue and to flee sin. So highly and profoundly was he learned in Divinity that he was, and is at this day, well known, esteemed, and reputed and allowed (and no less worthy) not only for one of the chiefest flowers of Divinity that lived in his time throughout all Christendom. Which hath appeared right and well by his works that he wrote in his maternal tongue, but much more by his learned and famous books written in the Latin tongue.

LUTHERANISM REFUTED

While unwavering in his fidelity to and defence of the Church, Fisher made no attempt to defend the indefensible behaviour of many churchmen from the pope downwards. The scandalous pontificate of Alexander VI (died 1503) was still fresh in men's minds. The manner in which Pope Leo X (1513-1521), Giovanni de Medici (son of Lorenzo the Magnificent) regarded his sacred office was made clear by his words: "Let us enjoy the papacy since God granted it to us." Leo X had one main aim in life, the aggrandizement of his family, which had long been the motivating force of the Medicis. "Had he remembered his office rather than his family and taken reform more seriously than politics, the Reformation might indeed have been a renewal of the Church instead or a terrible schism. As it was, one of the last chances of a truly Catholic reformation was lost." 14

In a book refuting Lutheran errors written in 1522, Fisher provided an accurate summary of the criticisms being made of Rome, particularly the life-style of the Curia. The Lutherans, wrote Fisher, claim that:

Nowhere else is the life of Christians more contrary to Christ than in Rome, and that, too, even among the prelates of the Church, whose conversation is diametrically opposed to the life of Christ Christ lived in poverty; they fly from poverty so far that their only study is to keep up riches. Christ shunned the glory of this world; they will do and suffer everything for glory. Christ afflicted himself by frequent fasts and continual prayers; they neither fast nor pray, but give themselves up to luxury and lust They are the greatest scandal to all who live sincere Christian lives, since their morals are so contrary to the doctrine of Christ, that through them the name of Christ is blasphemed throughout the world.

Fisher makes no attempt to deny the truth of these allegations, but with sound theological insight and masterly debating skill, he uses these scandalous facts to refute the Lutherans and demonstrate the Divine nature of the Church:

This is perhaps what an adversary might object, but all this merely confirms what I am proving. For since the Sees of other Apostles are everywhere occupied by infidels, and this one only that belonged to Peter yet remains under Christian rule, though for so many crimes and unspeakable wickedness, it has deserved like the rest to be destroyed, what must we conclude but that Christ is most faithful to His promises since He keeps them in favour of His greatest enemies, however grievous and many may be their insults to Him. 15

Fisher saw clearly that a distinction must be made between the Church and churchmen. The Church had been founded by Our Lord Jesus Christ Who would be with it all days until He comes again in glory to judge the living and the dead. His teaching has been preserved faithfully in the Church from the very beginning, above all in the teaching of the Fathers of the Church. In breaking away from this unbroken tradition Luther deprives himself of any credibility. Of all Luther's works, the bishop insisted, none was "more pestilential, senseless, or shameless" than The Abrogation of the Mass. In this book Luther "tries utterly to destroy the sacrifice of the Body and Blood of Christ, which the Church has ever held to be most salutary, and the chief object of devotion to all the faithful of Christ." Fisher quotes with indignation Luther's arrogant insistence that his three arguments against the sacred priesthood cannot be refuted:

I am convinced that by these three arguments every pious conscience will be persuaded that this priesthood of the Mass and the Papacy is nothing but a work of Satan, and will be sufficiently warned against imagining that by these priests anything pious or good is effected. All will now know that these sacrificial Masses have been proved to be injurious to our Lord's testament and that therefore nothing in the whole world is to be hated and loathed so much as the hypocritical shows of this priesthood, its Masses, its worship, its piety, its religion. It is better to be a public pander or robber than one of these priests. 16

The saintly bishop cannot contain his indignation at these blasphemies:

My God! How can one be calm when one hears such blasphemous lies uttered against the mysteries of Christ? How can one without resentment listen to such outrageous insults hurled against God's priests? Who can even read such blasphemies without weeping from sheer grief if he still retains in his heart even the smallest spark of Christian piety?

Trusting therefore in the goodness of our Lord we will in our turn try to launch three attacks against Luther by which as with a sponge we hope to wipe away all the filthy and blasphemous things that have proceeded from his mouth against priests. 17

Fisher's indignation here provides an invaluable insight into his character. When the time came for him to be insulted and subjected to outrageously unjust treatment he exercised what must be described as almost supernatural restraint and humility. When the Faith which he loved more than his life was attacked he could show no such restraint. In his reply to Luther the bishop displays the full extent of his scholarship, quoting profusely from the Scriptures and the Fathers of the Church. 18 Time and again he emphasizes that the argument from Tradition is unanswerable:

Whereas the truth of the priesthood is abundantly and unanimously witnessed to by all the Fathers through the whole history of the Church, and whereas there is no orthodox writer who is not in agreement, and no word of Scripture that can be qupted against it, therefore all must clearly see how justly, against Luther, we claim the truth of the priesthood as the prescriptive right of the Church.

It would indeed be incredible that when Christ had redeemed His Church at so great a price, the price of His Precious Blood, He should care for it so little as to leave it enveloped in so black an error. Nor is it any more credible that the Holy Ghost, Who was sent for the special purpose of leading the Church into all truth, should allow it for so long to be led astray.

Nor is it credible that the prelates of the Church, who were so numerous even in the earliest period of her history and who were appointed by the Holy Ghost to rule her, as we shall afterwards prove, should have been enveloped in such darkness through so many centuries as to teach publicly so foul a lie.

Finally, it is beyond belief that so many churches throughout the various parts of Christendom, hitherto governed with such careful solicitude by Christ and His Spirit and by the prelates appointed for the purpose, should now unanimously fall into an error so foul and a lie so ruinous, according to Luther, that it does an injustice to the very testament of our Lord. 19

In a subsequent book, De Veritate Corporis, Fisher refuted an attack on the Real Presence by the Lutheran theologian Joannes Oecolampadius who claimed that the words "This is My Body" are purely figurative, which did not correspond with Luther's doctrine of consubstantiation in which the true Body of Christ co-existed with bread after the consecration. This was but one example of the serious divisions that were already appearing within the Lutheran sect. Luther had replaced the infallible teaching authority of the Church by his self-bestowed personal infallibility in interpreting the Bible. In theory, he conceded the right of every believer to do this: "In matters of faith each Christian is for himself pope and Church, and nothing may be decreed or kept that could issue (result) in a threat to faith." 20 But in practice it was Luther's interpretation which must be accepted: "He who does not accept my doctrine cannot be saved. For it is God's and not mine." 21 Luther most certainly did not believe in universal freedom of opinion in religious matters. What he demanded was freedom for his own opinions. [Emphasis added.] Those who disagreed with him, whether Catholic or Protestant, were dismissed as "pig-dogs", "dolts", "fiends from Hell". His interpretation of the Bible was the saving truth, all else was lies and delusions. It is hardly surprising that some Reformers who disagreed with him remarked sardonically that it was small gain to have got rid of the pope of Rome if they were to have in his place the pope of Wittenberg. 22 Fisher did not simply take satisfaction in the divisions among Lutherans. He states specifically in his refutation of Oecolampadius that he exulted in it:

Yet it was not even on account of this vengeance of God abandoning them to a reprobate sense that I exulted. There is a still more evident proof of God's avenging hand. It is related in the Book of Genesis of certain men that they resolved to build a tower, whose top should reach to Heaven, so as to leave their names famous to posterity. The world was then of one tongue, but God so punished their pride as to confound their speech, so that one understood not the other. The same punishment has befallen these factious followers of Luther. They also had conceived in their minds that they would build a new Church, and get fame throughout the world. And in this endeavour it is wonderful how united they were and banded together, so that they seemed to be like one man, with one heart and mind. Nor would they have ceased from their work, had not God, pitying His Church, looked down from on high, and bridled their madness by strife of tongues. He has brought it about that those who seemed leaders and columns among them understand not each other's voices. They strive with one another, and no one deigns to listen to his neighbour. The followers of Carlstadt have separated from the Lutherans, and they are pouring out insults one against the other. It may be seen, from letters just printed in the name of Luther, how great a controversy rages. Even Melanchthon, as I have heard from trustworthy men, is not well agreed with Luther. And now at length another of these leaders comes to the front, named John Oecolampadius, who formerly followed Luther in everything, and now he most vehemently differs from him in many points . . . Who then does not see that God is fighting for His Church, since He has put confusion in their tongues and turned their arms one against the other.

10. The Roman name for Rochester was Durobrivæ or Durobrivis, contracted into Roibis, to which the Saxons added ceaster (from the Latin castrum---a fortified place). Thus it became Hroveceaster, or Rochester. The ecclesiastical name for the city is Roffa, and the Bishop of Rochester would sign himself as Roffensis. John Fisher signed himself as John Roffensis, abbreviated as JO. ROFFS.

11. J. Lortz, How the Reformation Came (New York, 1963), pp. 93-94.

12. The title was given to the king personally without any intention of making it hereditary, but Henry retained it after his breach with Rome, it was annexed to the Crown in 1543 by act of Parliament, made hereditary, and can still be found on British coins today, abbreviated as F.D.

13. Luther was a member of the order of Augustinian Hermits or Friars. This order was founded under Pope Alexander IV in 1256 by banding together, in the interests of ecclesiastical efficiency, several Italian congregations of hermits. Their rule was that of St. Augustine with a constitution modelled on the Dominicans.

14. E. John, The Popes (London, 1964), p. 328.

15. Convulsio calumniarum Ulrichi Minhoniensis quibus Petrum numquam Romæ.

16. J. Fisher, The Defence of the Priesthood, translated by Mgr. P. E. Hallett (London, 1935), p. 2.

17. Ibid., pp. 2-3.

18. In his controversies with Luther and other Protestants, particularly Oecolamapadius, there is scarcely a Greek or Latin writer from the first to the 13th century from whom he does not make apt citations.

19. Fisher, op. cit., pp. 18-19.

20. D. Martin Luthers Werke (Weimar, 1833), vol. V; p. 407.

21. Ibid., vol. x, p. 107.

22. A. Hilliard Atteridge, Martin Luther (London, 1940), p. 10.

-

21-06-07, 22:37 #7**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

Excerpts, Part Part 5: The English Reformation

It might have been hoped that, with a monarch who had been designated Fidei Defensor by the Pope, the Church in England would be spared the ravages inflicted upon Catholicism in continental Europe. This was not to be the case, but the reason for the Reformation in England was radically different than that for the Reformation in Europe. The difference is that whereas Martin Luther wished to change his religion Henry VIII wished to change his wife, and despite his apparent devotion to the Church the king based his conduct on one fundamental axiom, namely that because he was the king he must have his way. It has been said that history is written by the victors, and for centuries there prevailed a politically correct view of the English Reformation, written by the victorious Protestants, in which the significance of Henry's insistence upon marrying Anne Boleyn is minimized. The Protestant claim, based on the writing of John Foxe, is that because the Reformation happened it must have been necessary and therefore must have been wanted by the people. On the contrary, the best scholarship in the second half of this century has proved this to be untenable. It happened not because it was wanted by the people, but because it was imposed as an act of state. When Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509 Catholicism was probably more flourishing in England than anywhere in Europe: "With a rising level of recruitment to the priesthood, a buoyant market for religious books, and more and more altars and images crammed into the churches, Catholic pietywas flourishing in the years immediately before the Reformation." 23 There was vigorous lay involvement in Church life through countless flourishing religious guilds and confraternities. 24 Professor J. J. Scarisbrick considers the unprecedented extent of church building and improvement to be of the greatest possible significance:

Medieval parish churches are one of the glories of England. No other country is more richly endowed. In the hundred and fifty years or so before the Reformation, the high noon of the perpendicular style, an average of two out of every three underwent at least one major building programme of this kind----whether they were humble village churches or grand fanes of town and city. Those who believe in the decline of the late medieval Church have to explain this widespread and enthusiastic building. 25

Despite the remarkable piety of the English laity they did not hesitate to criticise faults among the clergy. They were concerned less with moral lapses, which "were very rare", 26 than with what they perceived as the more frequent fault of avarice. Complaints were made that some priests refused to bury people until they had received gifts for doing so, and for not administering the Sacraments when they were asked. 27 Recent scholarship, based on the examination of episcopal visitations, has shown that such abuses were far less widespread than Protestant historians have claimed:

On the issues of clerical education, morality, and pastoral care, it has been demonstrated in a number of regional studies that deficiencies were exaggerated by earlier historians and that clerical standards apparently satisfied parishioners. . . . for every Cardinal Wolsey and every Prior More of Worcester there were hundreds of poorly-paid and hard-working curates. 28

HANS HOLBEIN, Saint Thomas More, 1527

HANS HOLBEIN, Saint Thomas More, 1527

St. Thomas More was among the most severe critics of clerical failings in the reign of Henry VIII, but in a detailed examination of More's writing upon this subject, Cardinal Gasquet shows that he rejected any suggestion that the clergy were as a body corrupt. 29 As More made clear, the principal weakness of the pre-Reformation Church was the extent to which many bishops saw themselves primarily as royal officials rather than spiritual shepherds, and this was reflected in the choice that, with the exception of Fisher, they would make when they were required to choose between the king and the pope.

Thomas More regretted the lack of discretion in choosing clerics, and represented this as one of the chief abuses of the Church in England. The higher clergy cared little about possessing the qualities necessary for their state. Since Henry VII's days a bishop had become a royal official drawing a pension from Church revenues; his cleverness had brought him to the king's notice, and he looked to the latter for preferment, and continued to serve him at Court by undertaking either embassies or diplomatic missions. His own diocese never saw him, except when he was worn out, aged, or in disgrace. 30

If the Protestant claim that because the Reformation in England happened it must have been both necessary and wanted is incorrect, then why did it take place? The answer is simple. The innovations in both doctrine and liturgy during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, and Elizabeth I were imposed on the people from above without any evidence of popular support for the changes among the people. The Protestant historian Sir Maurice Powicke accepts this unequivocally: "The Reformation in England was a parliamentary transaction. All the important changes were made under statutes, and the actions of the King as supreme head of the Church were done under a title and in virtue of powers given to him by statute." 31

The only instance of such popular support for religious change in England was for the restoration of the Catholic Faith during the tragically brief reign of Mary Tudor. Another Protestant historian, Professor S. T. Bindoff notes that soon after Mary's accession to the throne in 1553: ". . . the Mass was being celebrated in London churches 'not by commandment but of the people's devotion', and news was coming in of its unopposed revival throughout the country." 32 Catholicism flourished once again in Mary's reign:

Altars, images, crucifixes and candlesticks were restored to the churches with alacrity, and the extent of local investment in service equipment suggests religious enthusiasm rather than reluctant conformism. . . . prospects for the future seemed good. In parish churches at least, the damage done by the Reformation was repaired, and clerical recruitment boomed again for the first time since the 1520s. In despair, Protestant writers in exile called for rebellion to overturn Mary's regime before the reconstruction of Catholicism became irreversible. 33

23. C. Haigh, The English Reformation Revised (Cambridge, 1987), p. 8.

24. E. Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars (Yale University Press, 1992), Chapter 4. This is the best documented study available of the vibrant, English Catholicism before the Reformation, and of the devastating effect on popular piety resulting from state imposed Protestantism.

25. J.J. Scarisbrick, The Reformation and the English People (Oxford, 1984), p. 13.

26. Haigh, op. cit., p. 3.

27. G. Constant, The Reformation in England (London, 1934), p. 15.

28. Haigh, op. cit., pp. 57-8.

29. A. Gasquet, The Eve of the Reformation (London, 1900), p. 136.

30. Constant, op. cit., pp. 19-20.

31. M. Powicke, The Reformation in England (Oxford, 1953), p. 34.

32. S.T. Bindoff, Tudor England (London, 1952), p. 168.

33. Scarisbrick, The Reformation..., op. cit., p. 9.

-

21-06-07, 22:38 #8**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

Excerpts, Part 6: A Zealous Pastor

The Bishop of Rochester did not content himself with condemning abuses in the Church whether in England or far-away Rome, but spared no pains in rooting them out in his own diocese. His constant journeys about his diocese were undertaken for the discovery of abuses as well as for the consolation and help of the unfortunate. He was never mealy-mouthed when he lit upon injustice or idleness or avarice. He wrote that: "Bishops be absent from their dioceses and parsons from their churches . . . We use by-paths and circumlocutions in rebuking, we go nothing nigh to the matter and so in the mean season the people perish with their sins." He also insisted that: "All fear of God, also the contempt of God cometh and is founded of the clergy." Any cleric with a guilty conscience trembled at the coming of the bishop who never hesitated to apply canonical penalties even to those with friends at Court. The diocesan registers of his episcopate have been preserved and prove him to have been a truly pastoral bishop. During his first twelve years at Rochester he carried out four visitations:

He carefully visited the parish churches in his own person; sequestering all such as he found unworthy, he placed other fitter in their rooms; and all such as were accused of any crime, he put to their purgation, not sparing simony and heresy. And he omitted neither preaching to the people, nor confirming of children, nor relieving of needy and indigent persons.

Everywhere the bishop went, he would preach to the people. When preaching to the ordinary faithful his style was simple and direct, avoiding rhetorical embellishments or the display of learning for learning's sake. His objective was that they should easily understand what he was saying, and that they should become better Catholics as a result of listening to him. After his sermon he would visit the sick in their homes, often mere hovels. A contemporary account reads:

He was in holiness, learning, and diligence in his cure and in fulfilling his office of bishop such that for many hundred years England had not any bishop worthy to be compared unto him. And if all countries of Christendom were searched, there could not lightly among all other nations be found one that hath been in all things the like unto him so well used and fulfilled the office of bishop as he did. He was of such high perfection in holy life and straight and austere living as few were in all Christendom in his time or any other.

Of his revenues of his bishopric which passed not yearly above 400 marks, he bestowed in deeds of charity all that remained after supplying the needs of his own household. He was not sumptuous but careful, according as might well become the reverent honour and degree of a virtuous bishop.

He studied daily long, and some part of the night He fasted very much, and prayed and meditated daily divers hours, and much part of the night also. He was much given to contemplation, and many years before his death never lay he on feather bed, but on a hard mattress. nor in any linen sheets, but only on woollen blankets . . .

He was of great, godly, stout courage and constancy, never dejected in adversity; nor elated with any prosperity; as one that put no trust in worldly things. Gentle and courteous too was he to all men, and very pitiful to them that were in any misery or calamity. He, like a good shepherd, would not go away from his flock, but continually fed it with preaching of God's word and example of good life. He like a good shepherd, did what he could to reform his flock, both spiritually and temporally, when he perceived any to stray out of the right way, either in behaviour or doctrine.

Fisher's concern for the poorest of his flock was unique among the English bishops of his time. Other bishops did indeed have alms distributed to the poor on their behalf; but this did not suffice for Fisher:

To scholars he was benign and bountiful, and in his alms to the poor very liberal as far as his purse extended, and himself visited his poor neighbours when they were sick, and brought them both drink, meat, and money. And many times to him that lacked he brought coverlet and blanket from his own bed, if he could find none other meet for the sick person.

Although the bishop regarded every minute of each day as precious, and regretted the time that courtesy demanded he should bestow upon the rich and important visitors who called on him on their way to and from London, he never begrudged the countless hours that he spent with the poorest of his flock:

Many times it was his chance to come to such poor houses as for want of chimneys were very smoky, and thereby so noisome that scarce any man man could abide in them. Nevertheless himself would then sit by the sick patient many times the space of three or four hours together in the smoke, when none of his servants were able to abide in the house, but were fain to tarry without till his coming abroad.

The bishop showed boundless solicitude for the dying. Hewould visit all who were likely to die, no matter how poor they might be, and teach them how to die as a Catholic should, and it was rare for him to leave without the sick person accepting death with true Christian resignation. The poor flocked to his gate each day, and always received money and food according to their need.

The most evident charact~ristic of Fisher's manner of dealing with heretics arrested within his own diocese was the intention of saving the sinner rather than condemning him. All those brought before him abjured their heresy after he had reasoned with them, and there is no record of an heretic ever having been sent to the stake in the Diocese of Rochester while he was bishop.

For thirty years he went among his people until his gaunt figure was a familiar sight in the countryside. Men knew that if his eyes were always sad, his expression was seldom stern. It was pity for souls which motivated him, pity for these very souls who, were entrusted to his care and who relied on him to be taught God's truth. He could not bear to think of Our Lord's sacrifice on Calvary being wasted, even in one individual case. His long prayers during the silent night were often dedicated to pleading for the victory of truth and virtue. In a sermon preached in 1505 he prayed for bishops who would be true shepherds to their flocks:

Set in Thy church strong and mighty pillars, that may suffer and endure great labours----watching, poverty, thirst, hunger, cold, and heat----which also shall not fear the threatenings of princes, persecution, neither death, but always persuade and think with themselves to suffer, with a good will, slanders, shame, and all kinds of torments, for the glory and laud of Thy Holy Name.

In this passage he had, without realizing it, painted his own portrait and prophesied in detail the sufferings that would precede his Martyrdom. Geoffrey Chaucer's account of the poor parson in the Prologue to The Canterbury Tales could be seen as a description of Fisher, had it not been written eighty years before his birth:

A good man was ther of religioun,

and was a povre persoun of a toun,

But riche he was of hooly thoght and werk.

He was also a lerned man, a clerk,

That Cristes gospel trewely wolde preche;

His parisshens devoutly wolde he teche.

The poor parson was praised because he did not persecute parishioners who could not pay their tithes, but would share the little that he had with the poor. Although his parish covered a wide area he would never fail to visit even the furthest homes, come rain or thunder, even when sick himself; or suffering from some personal adversity. He provided a fine example to his flock by practising in his own life what he taught them in his sermons. ("This noble ensample to his sheep he yaf; that first he wroghte, and afterward he taughte.") This priest made no attempt to find a more lucrative position, but stayed with his flock so that no wolf might enter their fold: "He was a shepherde and noght a mercenarine." Despite his great personal virtue he was not disdainful to sinners, doing his utmost to lead them to Heaven by fairness and good example, but if a sinner was obstinate, no matter how high his position, he would receive a stinging rebuke: "Hym wolde he snybben sharply for the nonys." No better priest than this poor parson could be found, and the reason was because "Cristes loore and his apostles twelve he taughte, but first he folwed it hymselve."

In a tribute to Fisher, in which he insists that the Saint was the holiest bishop in Christendom, Cardinal Pole echoes Chaucer's description of the poor parson:

What other have you, or have you had for centuries, to compare with Rochester in holiness, in learning, in prudence, and in episcopal zeal? You may indeed be proud of him, for, if you were to search through all the nations of Christendom in our days, you would not easily find one who was such a model of episcopal virtue. If you doubt this, consult your merchants who have travelled in many lands; consult your ambassadors; and let them tell you whether they have anywhere heard of any bishop who has such a love of his flock as never to leave the care of it, ever feeding it by word and example; against whose life not even a rash word could be spoken; one who was conspicuous not only for holiness and learning but for love of country? 34

A MAN OF PRAYER

Like all great Saints, John Fisher realized that holiness cannot be achieved without regular and fervent prayer.

He never omitted so much as one collect of his daily service, and that he used to say commonly to himself alone, without the help of any chaplain, not in such speed or hasty manner to be at an end, as many will do, but in a most reverent and devout manner, so distinctly and treatably pronouncing every word that he seemed a very devourer of heavenly food, never satiate nor filled therewith. Insomuch as, talking on a time with a Carthusian monk, who much commended his zeal and diligent pains in compiling his book against Luther, he answered again, saying that he wished that time of writing had been spent in prayer, thinking that prayer would have done more good and was of more merit.

And to help this his devotion he caused a great hole to be digged through the wall of his church in Rochester, whereby he might the more commodiously have prospect into the church at Mass and evensong times. When he himself used to say Mass, as many times he used to do, if he were not letted (prevented) by some urgent and great cause, ye might then perceive in him such earnest devotion that many times the tears would fall from his cheeks.

John Fisher always lived an austere life, eating little, and only the plainest food, and sleeping for only four hours a night on a hard bed. There was no luxury in the furnishing of his great, damp palace, save perhaps in the number of books it housed. It is probable that his predecessors had neglected necessary repairs and improvement as they used the see as no more than a stepping stone to more lucrative bishoprics. Towards the end of his episcopate, he became a weak old man, racked with rheumatism, but even then he would never give up his preaching and sat in a big, upright chair to teach the people. Erasmus once wrote to him that his austerities were too great for his health. The great scholar could speak from first hand experience gained during his stay in the Bishop's Palace in August 1516 when he gave Fisher his preliminary instruction in Greek.

Your illness arises chiefly from the locality in which you live, the sea is near you, and a muddy shore, and your library is surrounded with glass windows which let in the keen air at every chink, and are very injurious to persons in weak health. I am quite aware what an assiduous attendant you are in your library which is your paradise; I should have a fit of sickness were I to stay in it three hours. A boarded and wainscoted chamber would be much better-brick and plaster give out a noxious vapour. It is important to the Church in the penury of good bishops, that you should take care of yourself.

The Protestant bishops who succeeded Fisher would not even consider living in the damp, unhealthy palace at Rochester, but had a brand new red brick palace built in Bromley where it can still be seen.

34. Pro Ecclesiasticæ Unitatis defensione, lib. iii.

-

21-06-07, 22:40 #9**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

Excerpts, Part 7: Anne Boleyn

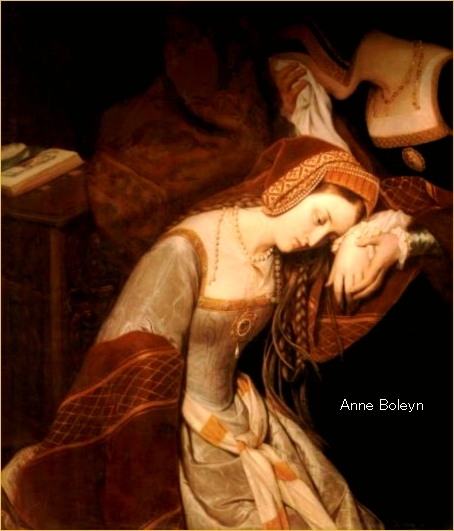

In 1521 the Lady Anne Boleyn returned to England after spending seven years at the French court in the household of Claude, queen of Francis I. She would have been about twenty-one years old at the time, the year of her birth is not certain, but it was probably 1501.

She was soon admitted to the household of Catherine as a maid-of-honour to the queen. The education that Anne had received at the French court gave her a superiority over her companions.

She could play, dance, and sing with more grace than any young woman in the English court. The Venetian ambassador described her as "not one of the handsomest women in the world", but noted that her eyes were "black and beautiful". Anne's portrait in the National Gallery shows that she was no great beauty. Despite this her vivacious personality and lively conversation attracted many admirers, including the king himself. Her sister Mary had been Henry's mistress only to be cast aside, as her predecessors had been.

Henry made it clear that he would like Anne to occupy this position, but the maid-of-honour, who was ten years younger than the king, insisted that if she could not be his wife she would not be his mistress. She consistently refused to succumb to his advances unless they were accompanied by a definite promise of marriage, and this unexpected resistance merely increased her attraction for him.

Father G. Constant noted the calculating manner in which she ensnared the king:

She played her game very skilfully----a crown was at stake----not only for a few months, but for nearly seven years. She yielded only when Henry was slipping downhill into schism with no hope of climbing back again, and only in order to hasten the conclusion of a scheme she had perseveringly worked out. 35

35. Constant, op. cit., p. 51.

-

21-06-07, 22:41 #10**********

- Data Registrazione

- 04 Jun 2003

- Messaggi

- 23,775

-

- 18

-

- 35

- Mentioned

- 2 Post(s)

- Tagged

- 0 Thread(s)

Excerpts, Part 8: Cardinal Wolsey

By an interesting coincidence, at the same time that Henry became infatuated with Anne Boleyn, he began to have scruples of conscience concerning his marriage with Qeen Catherine. His conscience was, he claimed, gravely troubled because by marrying his brother's widow he had violated Leviticus 20:21: "He that marrieth his brother's wife doth an unlawful thing." The king was, however, faced by the problem of Deuteronomy 25:5 which states: "When brethren dwell together, and one of them dieth without children, the wife of the deceased shall not marry to another; but her brother shall take her, and raise up seed for his brother." Henry claimed to be living in a state of torment for fear that his marriage was incestuous. He did not explain why he had lived happily with Catherine for seventeen years without being in the least troubled by such scruples.

The king had informed Cardinal Wolsey in March or April 1527 that he wished his marriage with Catherine to be annulled, but gave no hint that this was to make possible a marriage with Anne Boleyn (Wolsey was on terms of enmity with the Boleyns). The cardinal was aware of the fact that Anne had by then become the King's mistress, but took it for granted that, as in previous cases, he would eventually tire of her. Wolsey was under the impression that the bride the king had in mind was Renee, Duchess of Chartres, the daughter of Louis XII. She eventually married Hercule d'Este, Duke of Ferrara in 1528. Wolsey was not greatly concerned whether the marriage with Catherine was valid or invalid. He knew that Henry believed with almost dogmatic certainty that what he wanted must be right simply because he wanted it, and that to oppose him or to fail to obtain what he required was a form of treason. The marriage to Renee would help to perpetuate the alliance with France, Wolsey's principal objective in the diplomatic field. The cardinal offered the king his support and even ventured to promise complete success. The dispensation which enabled Henry to marry Catherine was only the third of its kind. In 1517 the Master-General of the Dominicans, Thomas De Vio (commonly called Cajetan), the greatest theologian of the sixteenth century, with the possible exception of Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, completed a lengthy examination of the problem, giving three examples of such dispensations, and citing that given to Henry and Catherine as the second. 36 Cajetan (who was made a cardinal in the same year) bases his conclusion on a fundamental principle of Catholic theology: Roma locuta est, causa finita ("Rome has spoken the dispute is finished"). The fact that the pope has dispensed in the three cases cited, insists Cajetan, proves that he has the power to do so. So fundamental is this principle that, as Monsignor Philip Hughes comments: "Cajetan takes this for granted, and he takes it for granted too that all his readers will take it for granted." 37 Professor J. J. Scarisbrick stresses the fact that as the dispensation involved the plenitude of papal power its validity could not be called into question by anyone claiming to be a Catholic, even if it had been without precedent (which was not the case):

Had Julius's dispensation been unique it would still have had strength from the fact that it was the fruit of a plenitude of power, which was the master, not the servant, of academic opinion. To a thorough papalist the proof that the pope could dispense this impediment was the fact that he had done so. 38

It is important to note that Cajetan's conclusion is not put forward as a response to Henry's demand for an annulment, but was reached ten years before the king began to develop his case against the validity of his marriage.

JOHN FISHER IS CONSULTED

Wolsey realized that his entire future depended on obtaining the annulment, and he believed that the support of the universally revered Bishop of Rochester could be the deciding factor in securing that future. He wrote to Fisher explaining the concerns troubling the conscience of the king, thus involving him for the first time in the king's "Great Matter". The reply which the cardinal received, and despatched to the king on 2 June 1527, proved to be a great disappointment. Just as Fisher had not denied the truth of Luther's allegations concerning the scandals of papal Rome (supra), he made no attempt to deny that weighty theologians had denied the possibility of a valid dispensation for the impediment of affinity in the first degree collateral. But these theologians had put forward this thesis before popes had given dispensations in such cases, and Fisher, like Cajetan, had not the least doubt that this settled the matter: Roma locuta est, causa finita. The Bishop explained in his reply to Wolsey that after consulting the best authorities he had no difficulty in reaching a conclusion: