Syrian Socialist Nationalist Party

Lebanon Table of Contents

The Syrian Socialist Nationalist Party (SSNP) has been one of the most influential multisectarian parties in Lebanon. Its main objective has been the reestablishment of historic Greater Syria, an area that approximately encompasses Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel. Over the years the SSNP has often resorted to violence to achieve its goals.

The SSNP was founded in 1932 by Antun Saadah, a Greek Orthodox, as a secret organization. His party, very much influenced by fascist ideology and organization, grew considerably in the years after independence. In fact, in a survey taken in 1958 by the French newspaper L'Orient, the SSNP was said to have 25,000 members--at the time, second only to the Phalange Party. Concerned by its strength, the government cracked down on the SSNP in 1948, arresting many of its leaders and members. In response, SSNP military officers attempted a coup d'état in 1949, following which the party was outlawed and Saadah was executed. In retaliation, the SSNP assassinated Prime Minister Riyad as Sulh in 1951.

In the 1950s, although still banned, the SSNP renewed its activities fairly openly. During the 1958 disturbances, the SSNP militia supported President Shamun, who rewarded it by authorizing it to operate legally. But in December 1961, when another attempted coup by SSNP members failed, it was again outlawed and almost 3,000 of its members imprisoned. In prison, the party underwent serious ideological reform when certain Marxist and pan-Arab concepts were introduced into the party's formerly right-wing doctrine.

Since the 1960s, the party has become more leftist. Most of its members joined the Lebanese National Movement and fought alongside the PLO throughout the 1975 Civil War. But during this period the party suffered internal divisions and defections, and since then party unity has been elusive. In 1987 there were at least four separate factions claiming to be the authentic inheritors of Saadah's ideology. The two most important were led by Issam Mahayri, a Sunni, and Jubran Jurayj, a Christian. Each faction was trying to settle disputes by means of violence.

Lebanon - Syrian Socialist Nationalist Party

Risultati da 1 a 10 di 205

-

25-08-10, 15:01 #1AvampostoOspite

Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

-

25-08-10, 15:03 #2AvampostoOspite

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

The Swastika and the Cedar

In newly liberated Lebanon, the signposts on “the Arab street” point in opposite directions. The author’s experiences—he was buoyed by a huge rally for democracy in downtown Beirut, then beaten up by Fascist bullies—show how much this diverse society offers hope but is still threatened by the Syrian dictatorship next door.

by Christopher Hitchens

As Arab thoroughfares go, Hamra Street in the center of Beirut is probably the most chic of them all. International in flavor, cosmopolitan in character, it boasts the sort of smart little café where a Lebanese sophisticate can pause between water-skiing in the Mediterranean in the morning and snow-skiing in the mountains just above the city in the afternoon. “The Paris of the Middle East” used to be the cliché about Beirut: by that exacting standard, I suppose, Hamra Street would be the Boulevard Saint-Germain.

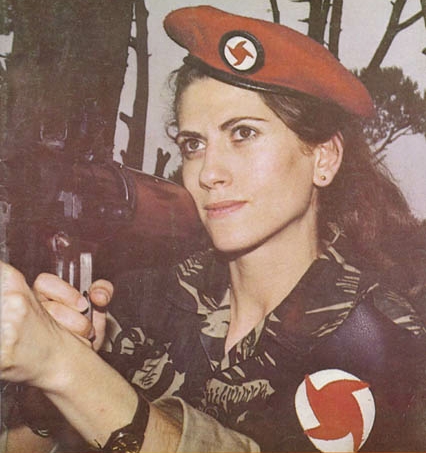

Not at all the sort of place you would expect to find a spinning red swastika on prominent display. Yet, as I strolled in company along Hamra on a sunny Valentine’s Day last February, in search of a trinket for the beloved and perhaps some stout shoes for myself, a swastika was just what I ran into. I recognized it as the logo of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, a Fascist organization (it would be more honest if it called itself “National Socialist”) that yells for a “Greater Syria” comprising all of Lebanon, Israel/Palestine, Cyprus, Jordan, Kuwait, Iraq, and swaths of Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt. It’s one of the suicide-bomber front organizations the other one being Hezbollah, or “the party of god” through which Syria’s Ba’thist dictatorship exerts overt and covert influence on Lebanese affairs.

Well, call me old-fashioned if you will, but I have always taken the view that swastika symbols exist for one purpose only to be defaced. Telling my two companions to hold on for a second, I flourish my trusty felt-tip and begin to write some offensive words on the offending poster. I say “begin” because I have barely gotten to the letter k in a well-known transitive verb when I am grabbed by my shirt collar by a venomous little thug, his face glittering with hysterical malice. With his other hand, he is speed-dialing for backup on his cell phone. As always with episodes of violence, things seem to slow down and quicken up at the same time: the eruption of mayhem in broad daylight happening with the speed of lightning yet somehow held in freeze-frame. It becomes evident, as the backup arrives, that this gang wants to take me away.

I am as determined as I can be that I am not going to be stuffed into the trunk of some car and borne off to a private dungeon (as has happened to friends of mine in Beirut in the past). With my two staunch comrades I approach a policeman whose indifference seems well-nigh perfect. We hail a cab and start to get in, but one of our assailants gets in also, and the driver seems to know intimidation only too well when he sees it. We retreat to a stretch of sidewalk outside a Costa café, and suddenly I am sprawled on the ground, having been hit from behind, and someone is putting the leather into my legs and flanks. At this point the crowd in the café begins to shout at the hoodlums, which unnerves them long enough for us to stop another cab and pull away. My shirt is spattered with blood, but I’m in no pain yet: the nastiest moment is just ahead of me. As the taxi accelerates, a face looms at the open window and a fist crashes through and connects with my cheekbone. The blow isn’t so hard, but the contorted, glaring, fanatical face is a horror show, a vision from hell. It’s like looking down a wobbling gun barrel, or into the eyes of a torturer. I can see it still.

And though I suppose in a way that I did “ask for it” this can happen on a sunny Saturday afternoon on the main avenue, on a block which I later learned has been living in fear of the S.S.N.P. for some time. In the morning, though, I had been given a look at a much more heartening version of “the Arab street.” Valentine’s Day was the fourth anniversary of the assassination, by a car bomb of military-industrial grade and strength, of the immensely popular former prime minister Rafik Hariri. A hero to millions of Lebanese for his astonishing rebuilding of the country (admittedly by his own construction consortium) after 15 years of civil war, he became a hero twice over when he resisted Syrian manipulation of Lebanese politics. (The statistical connection between that political position and the probability of death by car bomb is something I’ll come to.)

Martyrs’ Square, the huge open space in downtown Beirut, dominated by the finest imaginable Virgin Megastore and by a brand-new sandstone mosque in the Turkish style commissioned by Rafik Hariri, was absolutely thronged by a crowd of hundreds of thousands. Although it was a commemorative event, there were no signs of the phenomena that the media have taught us to expect when death is the subject in the Middle East. That is to say, there were no hoarse calls for martyrdom and revenge, no ululating women or children wearing suicide-bomber shrouds, no firing into the air or coffins tossing on a sea of hysterical zealotry. As I made my way through the packed crowd I wondered why it seemed somehow familiar. It came to me that the atmosphere of my hometown of Washington on the day of Obama’s inauguration had been a bit like this: a huge and unwieldy but good-natured celebration of democracy and civil society.

Lebanon is the most plural society in the region, and the “March 14” coalition, the group of parties that leads the current government, essentially represents the Sunnis, the Christians, the Druze (a tribe and creed unique to the region), and the Left. Hezbollah has a partial stranglehold on the Shiite community but by no means a monopoly, and one of the speakers at the rally was a Shiite member of parliament, Bassem Sabaa, who argued very strongly that Arab grievances against Israel should not excuse Arab-on-Arab oppression. Almost nobody displayed any religious emblem, and even the few who did were usually careful to put it next to the ubiquitous cedar-symbol flag of Lebanon itself. Women with head covering were few; women with face covering were nowhere to be seen. Designer jeans were the predominant fashion theme. Eclectic musical choices came over the loudspeakers. The average age was low. Nobody had been bused in, at least not by the state. Nobody had been told to leave work and demonstrate his or her loyalty. You get my drift.

This is the way that Lebanon could be: a microcosm of the Middle East where ethnic and confessional differences are resolved by Federalism and by elections. But there is a dark, supervising power that keeps the process under surveillance, and then alters the odds by selecting some actors for abrupt removal. As Omar Khayyám unforgettably puts it in his Rubáiyát:

’Tis all a Checker-board of Nights and Days

Where Destiny with Men for Pieces plays:

Hither and thither moves, and mates, and slays,

And one by one back in the Closet lays.

If you want to replace the word “Destiny” with a more modern term, you might get a hint from a banner that was displayed after the murder of Rafik Hariri. syrial killers, it read, simply. The street reaction to the murder of Rafik Hariri was so intense that it led to the passage of a United Nations resolution mandating the withdrawal of the Syrian Army from Lebanon after almost three decades of occupation. However, it remains the case that those who inconvenience Syria by their criticisms are bad liabilities from the life-insurance point of view. Since somebody’s car bomb killed Hariri and 22 others, somebody has killed Samir Kassir and Gibran Tueni, two of the bravest journalists and editors at the independent newspaper An-Nahar (The Day). Somebody has killed Pierre Gemayel, a leader of the country’s Maronite Catholic community. Somebody has killed George Hawi, a former leader of the Lebanese Communist Party. Somebody has killed Captain Wissam Eid, a senior police intelligence officer in the investigation of the Hariri murder.

The murders of these Lebanese patriots, and four others of nearly equal prominence, were all highly professional explosive-charge or hit-squad jobs, and their victims all had one, and only one, thing in common. In a highly unusual resolution, the United Nations has established a tribunal to inquire into the Hariri murder and its ramifications, four Lebanese former generals with ties to Syria have been arrested on suspicion, and an office in The Hague has already begun the preliminary proceedings. This investigation will condition the circumstances under which the next Middle East war involving Israel, Syria, Iran, and Hezbollah will take place on Lebanese soil.

Officially removed from that soil, Syria continues to manipulate by proxies and by surrogates. One of its projections of power is the S.S.N.P., the Christian Orthodox Fascist group with which I tangled (and which is thought to have provided the muscle in some of the abovementioned assassinations). Another, which is also part of the shadow thrown on Lebanon by Iran, is Hezbollah. Two days after the anti-Syrian rally, I journeyed to the Dahiyeh area of southern Beirut, where the “party of god” was commemorating its own martyrs. This is the distinctly less chic Shiite quarter of the city, rebuilt in part with Iranian money after Israel pounded it to rubble in the war of 2006, and it’s the power base of Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah, the brilliant politician who is Hezbollah’s leader.

The contrast between the two rallies could not have been greater. Try picturing a Shiite-Muslim mega-church in a huge downtown tent, with separate entrances for men and women and separate seating (with the women all covered in black). A huge poster of a nuclear mushroom cloud surmounts the scene, with the inscription oh zionists, if you want this type of war then so be it! During the warm-up, an onstage Muslim Milli Vanilli orchestra and choir lip-synchs badly to a repetitive, robotic music video that shows lurid scenes of martyrdom and warfare. There is keening and wailing, while the aisles are patrolled by gray-uniformed male stewards and black-chador’d crones. Key words keep repeating themselves with thumping effect: shahid (martyr), jihad (holy war), yehud (Jew). In the special section for guests there sits a group of uniformed and be-medaled officials representing the Islamic Republic of Iran. I remember what Walid Jumblatt, the leader of the Progressive Socialist Party and also the leader of the Druze community—some of my best frien

The Swastika and the Cedar

-

25-08-10, 15:05 #3AvampostoOspite

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Radical Politics and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party

by Daniel Pipes

International Journal of Middle East Studies

August 1988

Until now, there has appeared no party in the Arab world that can compete with the SSNP for the quality of its propaganda, which addresses both reason and emotion, or for the strength of its organization, which is effective both overtly and covertly. By virtue of its organization, this party succeeded in creating a very powerful intellectual and political current in Syria and Lebanon.

- Abu Khaldun Sati' al-Husri

To the extent they pay it attention, observers of Middle East politics tend to dismiss the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, or SSNP, as a historical curiosity. Over a period of four decades, for example, The Economist has called it many names. In 1947 it was "an activist right-wing movement of a slightly dotty kind"; in 1962, it was "lunatic fringe," "farcical," and "idiotic"; and in 1985, it was "an odd little organisation."' Michael C. Hudson, a scholar of Lebanese politics, termed the SSNP's politics "bizarre" and its ideology "thwarted idealism twisted into a doctrine of total escape."

There is reason for this disparaging treatment. From its founding in 1932 until the present time, the party has fallen short in virtually everything it attempted. Quixotic conspiracies, foiled coup attempts, and unpopular ideological efforts won it a reputation for ludicrous impracticality, and for not being serious. It always remained numerically very small and never got even close to power. In the SSNP record, frustration far outweighs achievement.

But the SSNP's failures should not obscure the fact that the party has had profound political importance in the twentieth-century history of Lebanon and Syria, the two states where it has been most active. It provided the minorities, especially the Greek Orthodox Christians, with a vehicle for political action. As the first party fully to embrace extreme ideals of the inter-war period, the SSNP incubated virtually every radical group on those two countries; it had, in particular, great impact on the Ba'th Party. Finally - and this may mark the apogee of its power-the government of Hafez al-Asad has allied with the SSNP and incorporated some of its ideas into Syrian state policy.

For these reasons, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party deserves to be better known and studied. While the account that follows does no more than sketch out the impact of the party, I hope that this appreciation may inspire more work on the SSNP. Research should not be difficult, for the SSNP is a party of intellectuals, and the organization and its membership have produced voluminous materials.'

Party And Ideology

The Syrian Social Nationalist Party (al-Hizb al-Suri al-Qawmi al-IjtimaLi) or SSNP has at times been known as the Syrian Nationalist Party or the Social Nationalist Party, both abbreviated as SNP; French mistranslations of its name are also used in English-the Parti Populaire Syrien or the Parti Populaire Social, abbreviated as PPS.

Antun Sa'ada (1904-1949), founder of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party.

Antun Sa'ada, a Greek Orthodox intellectual, founded the party in Beirut as a secret organization of students in November 1932. He served as the organization's leader until 1949; the party closely reflected his personality and his ideas. Majid Khadduri correctly observes that "never before in Syria's modern history had a leader possessed such conviction, vigilance, strength of character, and charisma" (and, it can be argued, none has followed him either). After 1949, the party has been led by mediocre figures, none of whom have been able to revive it to its former position.

The SSNP stands for three main tenets: radical reform of society along secular lines, a fascist-style ideology, and Greater Syria. Although best known for its Pan-Syrian ideology, a considerable portion of the party's appeal and influence had to do with its secular and fascist elements. Indeed, it is hard to say which feature had the most importance in attracting members.

The reform program is summed up in five principles: separation of church and state, prohibition of the clergy from interfering in politics, removal of barriers between sects, abolition of feudalism, and the formation of a strong army. The first three principles are secularizing-they call for the withdrawal of religion (i.e., Islam) from public life-while the latter two fit under the modernizing rubric. It should be kept in mind that while these views are common, even banal in the West, they struck Lebanese and Syrians of the 1930s as novel. Together, the reform principles constitute a social transformation that accounts for the second "S" in the party name.

A note of caution: because Sa'ada reflected the fascist thinking of the 1930s, the words "social" and "national" are sometimes joined together to form the combination "national socialist," Hitler's coinage and the basis of the word Nazi. This is a mistake, however, for Sa'ada used the word in Arabic for "social" (ijtima'i) not "socialist" (ishtiraki); the proper noun form for his ideology in English is not National Socialism but Social Nationalism.

The party's fascistic qualities were expressed in Sa'ada's exalted status, the party's organization, and its ideology, including the stress on blood lines and mystical nationalism. Party rituals imitated the fascists in many details, from the Hitler-like salute and the anthem set to "Deutschland, Deutschland iiber alles," to the party's symbol, a curved swastika called "the red hurricane." Before 1945, its fascist qualities offered both a powerful ideology and the means to side with the enemies of Britain and France, the two countries that ruled Greater Syria.

Fascists and Nazi sympathizers flocked to the SSNP as the only party in the Levant sympathetic to their viewpoint, and they appear to have formed a significant portion of the party's core membership. Some members were drawn by the fierce opposition to Communism. Others sought a strong leader, something Sa'ada offered in the fascist style of the 1930s. Adulation of Sa'ada was so extreme, the SSNP slogan during his lifetime was "Long live Syria! Long live Sa'ada!" There were also strong hints of his being the prophet of a new religion. SSNP recruits joined the party in a ceremony known as "baptism," at which they formally renounced other loyalties.

The third key characteristic of the SSNP is Pan-Syrian nationalism, the goal of building a Greater Syrian state. This requires some explanation. The exact definition of Greater Syria has varied at different stages of the party's history, but it always included the four modern states of Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan, as well as parts of Turkey. (Late in Sa'ada's life, he extended Syria to include the Sinai Peninsula, all of Iraq, and even Cyprus. The SSNP platform makes the unity of this area a central tenet. "[Greater] Syria is for the Syrians, and the Syrians are a complete nation." In contrast to the all-important Syrian nationality, the Arab, Muslim, Christian, Lebanese, and Palestinian identities are deemed inconsequential. This point of view pits the SSNP against Pan- Arabists and pious Muslims, as well as Lebanese and Palestinian separatists.

To create a state that represents the Syrian identity means eradicating the polities delineated by the British and French in the years after World War I-the Syrian republic, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan. Viewing these existing states as artificial and meaningless, the SSNP pays them no loyalty. With regard to Lebanon, for example, Sa'ada declared, "Above all, we are Pan-Syrian nationalists; our cause is the cause of [Greater] Syria, not that of Lebanese separatism." He argued that "Lebanon should be reunited with natural Syria" and explicitly stated that his goal was "to seize power in Beirut to achieve this objective."

To assess the import of Sa'ada's views on Greater Syria, it has to be understood that Pan-Syrianism has two forms, the pragmatic and the pure. Pragmatists and purists differ in their view of the great ideology of the central Middle East, Pan-Arab nationalism. The first group accepts it, the second rejects it.

Pragmatists contend that Greater Syria forms part of the Arab nation and its creation is a stepping stone toward a Pan-Arab polity. For them, the unification of Syria is not an end but a means toward building a much larger unit. King 'Abdallah of Jordan was perhaps the most prominent and articulate of the pragmatists. Purists seek something quite different: a Greater Syrian state complete in itself without reference to a larger union. For them, Syria has no connection to an Arab state. A pure Pan-Syrianist cannot accept Syria's submergence in a larger Arab entity. If Syrians are a nation, then the Arabs are not; Sa'ada argued that "the Arab world is many nations, not one." He scorned efforts to bring together the many nations of the Arabs as unfeasible and counterproductive.

A Pan-Arabist can accept the pragmatist's goal but must deny the purist's. Greater Syria is fine so long as it helps build the Arab nation; as an end in itself, it is anathema. The Pan-Arabist rejects the pure Pan-Syrianist view that Greater Syria has political significance in itself; in the words of Edmond Rabbath, "There is no Syrian nation. There is an Arab nation." Pure Pan-Syrianists disagree with Pan-Arabists on a host of other matters as well. Pan-Syrianists, for example, see the conflict with Israel as an internal Syrian affair in which the Arabs have no business. According to Sa'ada, "there is no need for Egypt or the Arabs to participate in the defense of Palestine." In contrast, Pan-Arabists see a direct role against Israel for every state between Morocco and Oman.

The Syrian Social Nationalist Party is virtually the only exponent of pure Pan-Syrianism. It does so with the knowledge that this position denies the validity of Pan-Arabism, a widely cherished political tenet. Sa'ada consciously adopted a very controversial position, one that distinguished the SSNP not only from general intellectual trends but even from the great bulk of Pan-Syrian nationalists. The disrepute of pure Pan-Syrianism goes far to explain why the SSNP is dismissed as eccentric; add the secularism and fascism, and its frequent persecution becomes understandable.

A Minority Movement

Why then did the SSNP adopt these unpopular principles? In part, because of the background of its founder and first leader, Antun Khalil Sa'ada. Born to a Lebanese Greek Orthodox family in 1904, Sa'ada spent the critical years of his youth outside Lebanon. His father, Khalil Sa'ada, lived in Egypt for several years before World War I and Antun joined his father in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in 1920. Although a medical doctor, the elder Sa'ada published a journal, al- Majalla, which promoted independence for Syria, secularism, and anti-confessionalism.

He also founded the National Democratic Party in Buenos Aires and chaired the first Syrian National Congress after World War 1. These influences clearly affected the theories of Antun Sa'ada, who returned to Lebanon in 1929 and founded the SSNP in November 1932. The family's years abroad, and especially those in Egypt, go far to account for the characteristic elements of Sa'ada's thought: his deep belief in a Syrian identity, his rejection of the Arab identity, and his secularism.

Syrians constituted a small but highly influential community in Egypt from the eighteenth century on. Although playing a major role in the country's commercial, industrial, and intellectual life, they never lost their separate identity or forgot their foreignness. To the contrary, the Syrians took pride in the many points of difference between them and the native population. As Egyptian nationalism grew in the late nineteenth century, the Syrians' sense of being apart became more acute. Thomas Philipp writes that "Syrians who had arrived during the last two decades of the nineteenth century had to realize that they would remain marginal and barely tolerated in Egyptian national politics. As emigrants in a foreign surrounding, they had, indeed, been made aware of their 'Syrianness.'"

The psychology of Syrians in Egypt bore on Khalil Sa'ada's and then Antun Sa'ada's ideas in several ways. First, Egyptians perceived all those from the Levant area as Syrians; if residents of Jaffa and Aleppo felt nothing in common before arriving in Egypt, they gained some sense of solidarity after living there a while. Second, in contrast to Syrians living in Greater Syria, who casually equated being Syrian with being Arab, Syrians in Egypt drew a sharp distinction between the two notions. Noting that Egyptians too speak Arabic, they tended to consider themselves Syrians, not Arabs. Sa'ada's views probably originated in this perception. Third, whether Muslim, Christian or Jewish, Syrians in Egypt felt a kinship for each other (in strict contrast to those who never left Syria) and organized themselves without much regard to religion. Sa'ada's effort to ignore religion as a political force may well have derived from this outlook.

Other reasons for the party's unpopular views had to do with the SSNP's appeal to non-Sunni minorities. Secularism offered them a level playing field, erasing their historic disabilities. Christians endured the indignities inherent in the dhimmi status; Shi'is suffered from centuries of persecution at Sunni hands.

For its part, pure Pan-Syrianism held up as an ideal a geographic unit in which non-Sunnis constitute about half the population; in contrast, they almost disappear in larger Arab units. By bridging the historic gap between Muslims and Christians, Pan-Syrianism promised full citizenship and equality for the latter; by glorifying pre-Islamic antiquity-the civilization that Islam vanquished-it celebrated the common past; and it offered a state that would include nearly all Orthodox Christians within its confines. (Being thinly spread through a large region, the Orthodox, unlike the Maronites, could not retreat to their own homeland; but this was one way to bring their whole community together.)

Choosing to appeal to minorities had a major drawback, of course; it rendered widespread Sunni Arab support impossible. Most Sunnis rejected secularism and pure Pan-Syrian nationalism, the two dimensions of the SSNP program. Secularism challenges some of the basic precepts of Islam; the few Muslim thinkers who have publicly espoused the withdrawal of religion from politics have been at best ignored, at worst put on trial and executed. Similarly, pure Pan-Syrianism violates the spirit of Islam. It disregards religious distinctions, equates non- Muslims with Muslims, glorifies pagan antiquity, and puts undue emphasis on the history, culture, and bloodlines of a territory. Extreme attachment to a piece of territory is un-Islamic-not precisely against the religious law, but very much against its spirit. (On the positive side, Pan-Syrianism does attract those few Sunni Arabs who reject Islamic ways and want to reach across the religious divide.)

The intense opposition of most Sunnis to pure Pan-Syrian nationalism doomed the SSNP's chances to achieve its ambitions. The Greek Orthodox (alone or in combination with other minorities) could not dominate a Greater Syrian state; even if they did, the experience of the Maronites-who tried to impose a minority ideology in Lebanon and failed-suggests they would not prevail for long.

But Sunnis were not the only ones to oppose the SSNP. Its violent, irredentist, secularist, and fascist qualities assured hostile relations with almost everyone. French authorities proscribed the party during the Mandate because it agitated for independence. Gamal 'Abdel Nasser of Egypt persecuted the SSNP because it opposed the 1958-1961 union with Egypt (a non-Syrian state). Israel fought the party because of its extreme anti-Zionism. Ba'thists rejected its pure Pan- Syrian ideology. Socialists and Communists opposed its fascism. Leaders of independent Lebanon suppressed the SSNP because it denied the state's legitimacy. Syrian rulers sought to silence a proven troublemaker.

Even the other foremost exponent of Greater Syria, King 'Abdallah of Jordan, battled the SSNP. He rejected its republican and secular ideas, its pure Pan- Syrian nationalism, and its claim to rule a future Greater Syrian state. In response, Antun Sa'ada took on 'Abdallah openly, declaring that "the SSNP has fought the Amman plan because of its ideology. We do not want a monarchy."' According to another SSNP figure, "we are against the king, for he wants to establish a state on religious bases." On one occasion, the SSNP even approved military cooperation between the Lebanese and Syrian governments to resist the king's Greater Syria plan.

The better to harass the SSNP, its many enemies frequently charged the party of collaborating with foreign powers and doing their dirty work. French authorities accused it of collaboration with the Axis powers in the 1940s; the Vichy government, ironically, continued to press this charge. Rumors of American subsidies-which subsequently were proven accurate-discredited SSNP candidates in the Syrian elections of 1953. Nasser later accused the SSNP of taking American money. A British hand was suspected behind the 1961 coup attempt in Lebanon. Talk in recent years has (with good reason) centered on Romanian and Soviet aid.

With so many enemies, it is not surprising to find the SSNP persecuted through most of its existence. Sa'ada himself was imprisoned twice by the French, in November 1935 and August 1936, and finally executed by the Lebanese police after a hasty trial. In Lebanon, the party frequently alternated between legality and illegality. It was banned for the first time in March 1936 and made legal in May 1937; banned in October 1939 and made legal by Camille Chamoun in May 1944; banned in July 1949 and made legal by Chamoun again in September 1958; banned in January 1962 and made legal by Kamal Jumblat in 1970. (It remains legal since 1970.) In Syria, the party was legal until 1955 (and so the party headquarters were in Damascus from 1949 to 1955) but has been banned since then. In Jordan, assassinations carried out by SSNP members caused it to be repressed during 1951-1952; and the Jordanian security services tried to eradicate the party in 1966.

Despite strong official disfavor, the SSNP has on occasion won representation in the Lebanese and Syrian parliaments. In Lebanon, it took one seat in the 1957 elections. It did better in Syria, winning nine seats in 1949, one in 1953, and two in 1954. Though far too few to pass any legislation, these representatives gave the party a platform to make its views more widely known.

Hiding The Message

But the SSNP has not always wanted its true views known. To protect itself from persecution, it has frequently resorted to stratagems for obscuring the message of pure Pan-Syrian nationalism. To use the language of Islam, the party in effect engaged in taqiyya (dissimulation to preserve the faith) of an ideological nature. It adopted a variety of covers, including pragmatic Pan-Syrianism, local patriotism, Leftist rhetoric, and even Pan-Arabism.

Sa'ada made pragmatic Pan-Syrian statements on occasion, touching up his plans for Greater Syria with specks of Pan-Arabism. He would portray the realization of Greater Syria as a step toward Arab liberation. "First the Social Nationalist revival of Syria, then cooperative politics for the good of the Arab world. The rise of the Syrian nation liberates Syrian power from foreign authorities and directs it toward arousing the other Arab nations, helping them progress." Sa'ada would go further, placing Syria in an Arab framework: the fact that "the Syrian nation [umma] is part of an Arab nation [umma] does not contravene its being a complete nation with right to absolute sovereignty."

Sa'ada also developed a peculiar concept, "the Arabism of Syrian Social Nationalism," which attempted to square the circle by postulating Syrian leadership of the Arabs." He went so far as to claim, "if there is a real, genuine Arabism in the Arab world, it is the Arabism of the SSNP," and used this to justify his argument that "the Syrian nation is the nation suited to revive the Arab world."

During the 1956-1967 period, when Pan-Arabism had attained the peak of its popularity, the party muted its Pan-Syrian goals. An SSNP leaflet proclaimed two contrary slogans on one page: "Syrian nationalism against Arab nationalism," and "The SSNP supports the Fertile Crescent, a historic and geographic reality, as the only valid form of union in the Middle East-without rejecting the possibility of an Arab front." This double message makes it hard to believe that the SSNP underwent a genuine change of heart; references to the pure Pan- Syrian ideas of old lead this observer to conclude that Sa'ada's vision remained at the heart of the SSNP ideology.

But hints of local patriotism can be found as early as May 1944, when loyalty to Lebanon served as a useful cover and the party stated its goal to be "the independence of Lebanon." Ten years later, to defend the status quo from the radical Pan-Arabist programs advocated by Nasser, the Ba'th and others, SSNP leaders adopted a pro-Western outlook and made common cause with conservatives. This tactic culminated in 1958, during the civil war in Lebanon, when the SSNP joined the Lebanese government to suppress the rebels; given the party's views on the illegitimacy of Lebanon's very existence, this was a remarkable stand. This too represented not a change in long-range goals but an appreciation of Lebanon as refuge; SSNP leaders rightly feared that a victory by the government's opponents would close the country to them.

But the real need for dissimulation came in 1962. As a result of the fiasco of December 1961, when it failed in an attempt to overthrow the Lebanese government, the SSNP found itself banned in Lebanon (as well as Syria). To become acceptable again in one or another of these states, it adopted three strategies. First, as in 1944, members feigned local patriotism. Those who lived in Syria pledged loyalty to the regime in Damascus; likewise, those in Lebanon portrayed themselves as devoted to the preservation of Lebanon's independence.

This tactic was tried out at the military tribunal set up to punish the participants of the failed coup, but had little success, as neither the public prosecutor nor the presiding judge were fooled. The former told the judge:

The object of the SSNP conspirators must be obvious to you and to all the world-it was none other than the implementation of the Party's basic principles [by taking power in Lebanon]. Lebanon was aware of this fact from the very beginning. But when the conspirators failed, they tried to fabricate reasons for their conspiracy, feigning concern for reform of the regime in Lebanon and for social development.

The judge concurred: "Its goal being contrary to the law, the SSNP acted like a secret society and did not reveal its real doctrine to the authorities. Instead, ... the party pretended to be working to preserve the Lebanese entity." The implausibility of this tactic seems to have led to its abandonment.

Second, the party abandoned fascist doctrines and adopted the more acceptable rhetoric of the Left. This transformation was completed by 1970 and permitted the SSNP soon after to make common cause with those groups seeking to overturn the status quo. Close relations were developed with several parties, especially the Progressive Socialist Party of Jumblat and the PLO. The move from Right to Left appears long-lasting; by 1984, the SSNP chief was attending the anniversary celebration of the Lebanese Communist Party. Those unacquainted with the party's ideology even see it as a Marxist What began as dissimulation may have, with time, become reality; the SSNP orientation today appears to be permanently aligned with the Left.

Third and most important, SSNP members took to portraying Greater Syria as the first step toward either a unified Arab front or (this was increasingly the case in later years) a single Arab nation. In other words, they adopted the protective coloring of pragmatic Pan-Syrian nationalism. One of the defendants at the 1962 tribunal of the SSNP declared that "the statement of faith in Greater Syria, in the Syrian nation [umma],... is the same as belief in the Arab nation." Syria constitutes a nation; the Arab front consists of many nationsincluding, preeminently, that of Syria. (When challenged by Pan-Arabists to drop all vestiges of Greater Syria, the SSNP refused, of course; it did so on the grounds that the formation of a Greater Syrian state represents a practical intermediate stage toward the realization of a single Arab nation.)

Although the mixing of Pan-Syrian and Pan-Arab themes became more consistent after 1962, it had long been standard Party taqiyya. Already in 1951, 'Isam al-Mahayiri, an SSNP member of the Syrian parliament, argued that "our work for the unity of Natural Syria [i.e., Greater Syria] is the cornerstone for every sound Pan-Arab building." Thirty-four years later, when Mahayiri was leader of the party, he still maintained the same dissimulation, telling an interviewer that the SSNP and Damascus "agree on clear Pan-Arab objective." In 1988, the contradiction remains: despite firmly held and well-known positions, the SSNP brandishes a slogan of "Commitment to the party's policy of struggle and pan-Arabism."

(continua)

Radical Politics and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party :: Daniel Pipes

-

25-08-10, 15:06 #4AvampostoOspite

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Incubating Radical Politics

Much of the SSNP's importance lies in its influence over a wide range of radical elements in Lebanon and Syria.

From its inception, when Sa'ada spent time inveighing at students at the American University of Beirut, the party attracted mainly an educated elite in Lebanon and Syria. It was the first party in the region to articulate a radical, secularist position without equivocation or ethnic bias. For many of the brightest and most ambitious young minds, this quality made it stand out during the twenty or so years after its founding in 1932. Though always numerically very small (estimates range between 120 to under 1,000 members in 1936), an impressive list of former members went on to become major figures in Lebanese and Syrian life. Ghassan Tuwayni became a powerful Lebanese publisher and politician.

Elie Salem became foreign minister. Fayiz Sayigh left the party to become an articulate spokesman of Pan-Arabism, while Hisham Shirabi became a leading Palestinian nationalist. One of Syria's most durable military dictators, Adib Shishakli (1949-1954), was a former member; a second, Salah Jadid (dictator from 1966-1970) was possibly also a member. As head of state, Shishakli remained close to SSNP members, including his brother Salah al-Din and 'Isam al-Mahayiri. In cultural life too, the party had a great impact; for example, the poet Adonis ('Ali Ahmad Sa'id) identified with the party in his youth.

As a well-organized and highly disciplined organization with a clear doctrine and an authoritarian leader, the SSNP had strengths others sought to copy. A number of former members took what they learned from it about political organization to begin their own parties. These included:

(1) Jumblat, the Druze leader in Lebanon, founded the Progressive Socialist Party in 1949 after negotiations to cooperate with the SSNP fell through.

(2) Shishakli modeled the Arab Liberation Movement (founded in August 1952) on the SSNP.

(3) Akram al-Hawrani, a leading figure in Syrian politics for many years, was one of the SSNP's first members. During his open association with the party, in 1936-1938, he helped found the National Youth Party and then in 1939 became its leader. Not only did Hawrani himself secretly remain a member of the SSNP but he also affiliated the National Youth Party with it. Hawrani eventually broke with the SSNP and cut ties between the National Youth Party and the SSNP. As in Jumblat's case, negotiations for cooperation with the SSNP failed, so Hawrani turned the National Youth Party into the Arab Socialist Party in January 1950. This latter organization remained independent only three years, being eventually merged with the Ba'th Party in February 1953.

(4) The SSNP found a wide following among Palestinians in the early 1950s, a number of whom subsequently held high positions in al-Fath, the Palestinian organization. Sa'ada's son-in-law, Fu'ad Shimali, had a key role in Black September. Bashir 'Ubayd worked closely with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Ahmad Jibril headed his own organization, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command. Georges Ibrahim 'Abdallah quit the SSNP in 1965 to join with George Habash's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

(5) In 1979 or 1980, 'Abdallah went on to found his own organization, the Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Fraction (known by its French acronym, FARL), most of whose members came from the SSNP. FARL worked with Syrian intelligence and was held responsible for a rash of terrorist acts in France during the 1980s. Even without a direct personal connection, the SSNP often provided a model for other political parties. The Phalanges Libanaises, the leading Maronite organization founded in 1936, adopted much from the SSNP; so too did al- Najjada, the Sunni organization founded a year later. Before establishing the Ba'th Party, Michel 'Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar apparently had long conversations with Sa'ada.

The Pan-Arab theorist Abu Khaldun Satic al-Husri, no friend of the SSNP, explained the reasons for this influence in the early 1950s: "Until now, there has appeared no party in the Arab world that can compete with the SSNP for the quality of its propaganda, which addresses both reason and emotion, or for the strength of its organization, which is effective both overtly and covertly. By virtue of its organization, this party succeeded in creating a very powerful intellectual and political current in Syria and Lebanon." Before the SSNP, political parties in Syria and most of the Middle East represented personal interests, even if they pretended to pursue causes; the SSNP was the first true indigenous party of an ideological nature. A historian of political parties in Syria is, therefore, correct to conclude that the SSNP was founded on "a completely different basis from the parties that preceded it or followed it."

The radicalism of the SSNP profoundly affected the nature of Pan-Arab nationalism. Elsewhere in the Arab world-Arabia, Egypt, and the Maghrib- Pan-Arabism first developed as a modest doctrine advocating harmonious political relations and cooperation in finances, culture and other spheres (what is known as moderate Pan-Arabism). But in Greater Syria, Pan-Arabism meant something far more ambitious and disruptive: the elimination of borders and the fusion of peoples (or radical Pan-Arabism). It appears that this latter idea can be traced back to the SSNP, whose plans to dismantle the boundaries dividing Greater Syria were subsequently transferred to the Arab nation. The Ba'th adopted SSNP-style principles in the late 1940s and then disseminated these to Egypt and throughout the Arabic-speaking countries. Radical Pan-Arabism flourished from about 1958 to 1967 and had vast political importance in the Middle East during that period. Although since overtaken by moderate Pan- Arabism, the ideology still lives on for some leaders, such as Mucammar al- Qadhdhafi of Libya.

In addition to its ideology and organization, the SSNP's devoted paramilitary forces gave it a capable militia which played a significant role in both Lebanese civil wars. In 1958, these stood with the government of Chamoun against the rebels. By the time fighting began in 1975, the SSNP had switched sides and played a small but important place in the anti-government coalition.

The SSNP has inspired many efforts to unify countries. In 1949 alone, it had connections to the three Syrian military rulers who pursued unity negotiations with Iraq, though each of these changed his mind or was overthrown before agreements could be reached. The SSNP's willingness to use subversion and violence won it powerful allies. On at least three occasions it received external outside backing for planned revolutions. Syria helped a 1949 attempt to overthrow the Lebanese government; 'Abd al-Illah, uncle of the king of Iraq, supported the SSNP in an unsuccessful 1956 effort to overthrow the government of Syria; and Lebanese military officers joined the December 1961 putsch against their own government. (The British government may also have had a role in this last effort.) Like almost all that the SSNP did, these incidents came to nought.

Even in failure, each of these had far-reaching consequences. Take the 1949 episode: In June of that year, the ruler of Syria, Husni al-Za'im, offered Antun Sa'ada a warm welcome and promises of arms against the Lebanese authorities.

This encouraged Sa'ada to declare war on them and to take steps to overthrow the government. But Za'im betrayed Sa'ada in July 1949 and delivered him to the Lebanese police, who immediately had him executed. Za'im's treachery had wide consequences in Syria and Lebanon. In Syria, it contributed to Za'im's overthrow a month later, for many Syrians were offended by Za'im's breach of promise. The director-general of Za'im's police, Shishakli, provided important assistance to the coup and soon after took power himself. Za'im lost his life at the hands of a soldier avenging Sa'ada. In Lebanon, Riyad al-Sulh, one of the great figures of Lebanese politics and the premier at the time of Sa'ada's death, was assassinated by an SSNP member in July 1951. Za'im's actions engendered an ill will toward Damascus that harmed Lebanese-Syrian relations for years. In both countries, the SSNP benefited from a backlash of sympathy.

An SSNP attempt to overthrow the Syrian government in April 1955 failed (of course), but it had a key role in the subsequent turn of Damascus toward the Soviet Union. The party had a prominent part in the events that led up to the Lebanese civil war breaking out in 1975.

From the late 1940s on, the Ba'th party was the SSNP's closest rival in Syria. It offered a similar set of attractions to roughly the same constituency. The history of these two parties is, to say the least, tangled. Perhaps the most striking thing is that, after engaging in a rivalry that culminated in open feuding during the late 1950s, they became steadfast allies twenty years later.

The Ba'th Party was founded in the 1940s by two Syrian teachers from Damascus, Michel 'Aflaq and Salah ad-Din al-Bitar. The party promoted a radical Pan-Arabist ideology calling for the elimination of existing Arab states and their replacement by a single Arab nation. The Ba'th emerged as a major force in Syria in 1957 and members of the party have ruled Syria since 1963 (and Iraq since 1968).

In their early years, the SSNP and the Ba'th Party shared a similar base of membership and means of recruitment. They competed for adherents primarily among the educated, radically minded non-Sunni minorities. Members tended to be lower-middle-class students with ex-peasant fathers newly arrived in a town. This said, the Ba'th seems to have had a more urban and Sunni makeup.

Both recruited heavily in government district high schools (which were elite institutions at that time), especially in the predominantly 'Alawi region of Latakia and the Druze region of Jabal Druze. Occasionally, as in Latakia during the 1940s, the two parties sponsored rival high schools. Both relied on teachers to spread their ideas. The Ba'th claimed as many as three-quarters of the high school students in Aleppo and its cells were active in all parts of the country by the late 1940s. Between them, they blanketed all the high schools of Syria.

According to Michael H. van Dusen, "by the early 1950s, there was not a single high school graduate who had not had some exposure to the Ba'th Party or SSNP while in school."

Both parties advocated a program calling for secularism and state control of the economy. Secularism has a self-evident appeal for peoples long persecuted on account of their religious beliefs. State control of the economy (whether the SSNP's fascist version or the Ba'th's socialist one) held out the promise of economic opportunity.

The two shared much else in common, including: elite membership (as late as 1963, the Ba'th reportedly had only 400 members); a reliance on conspiratorial methods; a vision of binding the peasants to the middle classes through industrialization; and a hope of fomenting revolution by mobilizing and enfranchising the dispossessed. And, very important for the future of Syria, both continued to influence military officers who had been party members as high school students; whereas the lower ranks mostly supported the SSNP, officers gravitated toward the Ba'th.

Members of the poorer and weaker religious communities in Lebanon and Syria found these two parties attractive and joined them in disproportionately large numbers. Indeed, it was not uncommon for members of the same family to split allegiance between the SSNP and the Ba'th. The Jadids, an 'Alawi family, were a prominent example. Two brothers, Ghassan and Fu'ad, participated in the SSNP's April 1955 assassination of the Ba'th officer 'Adnan al-Maliki, resulting in Ghassan's murder and Fu'ad's imprisonment; a third brother, Salah, had apparently been an SSNP member before joining the Ba'th Party and rising to become ruler of Syria in the late 1960s.

Initially, the SSNP had greater success than the Ba'th, for while both received 'Alawi backing, the SSNP also attracted Orthodox Christians. Both parties expanded in membership and influence in the early 1950s. The Ba'th caught up with the SSNP about this time and passed it a few years later. The disparity grew henceforth, with the Ba'th eventually become the ruling party in two states while the SSNP remained a small and widely despised movement. In retrospect, it appears that the Ba'th Party ultimately had to vanquish the SSNP. Temperamental, intellectual, organizational, and tactical factors help explain its greater success.

Temperamentally, the two parties differed in their willingness to accommodate a wider public, especially the Sunnis. Whereas Sa'ada followed his own logic to its conclusion, Aflaq and Bitar molded their ideology to prevailing currents. Ba'th leaders made some effort to attract Sunni Muslims; those of the SSNP did not. For this reason, most Sunnis could not stomach the SSNP. Joining the SSNP was always a more radical act than joining the Ba'th because the SSNP rejected tradition entirely in its quest for a new order. This contrast can be seen with regard to Pan-Arabism, Islam, and the role of religion in politics.

The SSNP's adamant rejection of Pan-Arabist nationalism very much diminished its appeal. Pan-Arabism feels congenial to Sunnis. Much of its draw lies in the compromise Pan-Arabism offers between the old aspiration to Islamic solidarity and the modern drive for nationhood. Pan-Arab nationalism upsets Muslims less than other kinds of nationalism (including the Pan-Syrian variety) because it conforms to many views commonly found among Muslims and can be grounded in Islamic sensibilities. Fueled by Nasser's charisma, Pan-Arabism gained enormous popularity in the 1950s and the Ba'th gained accordingly.

The two parties' treatment of Islam offers an even more striking contrast in attitude toward Sunni participation. The SSNP transformed Islam into something unrecognizable to a Muslim. According to Sa'ada, Islam has two manifestations, Christianity and Muhammadanism; these are not two distinct religions but two versions of the same religion. Sa'ada replaced the usual doctrines of Islam with new ones based on the principles of Social Nationalism; the resulting religion shared next to nothing with mainstream Islam. This bizarre view, expounded in Sa'ada's Islam in Its Two Messages: Christianity and Muhammadanism, attempted to bring Christians and Muslims together at the same time that it denigrated the substance of their faiths.

By comparison, the Ba'th view of Islam was almost conventional. 'Aflaq saw Muhammad the Prophet not as a religious leader but as an outstanding Arab national figure and emphasized Islam's integral role in the formation of Arab culture. This interpretation, which reduced Islam to a non-spiritual tradition, offended pious Muslims; but it did neatly integrate Islam into Pan-Arabism. Further, it compelled non-Muslim Arabs to pay homage to Islamic culture, and in this way brought the two together. The Ba'th thus showed some respect for Islam and aligned itself with Muslim sensibilities. The resulting program was far less offensive to Sunni sentiments than that of the SSNP.

Ba'th and SSNP secularist doctrines also repelled the Sunni Arab majority, for secularism runs contrary to the traditional interpretation of Islam; but again the Ba'th was more in harmony with the sentiments of Sunni Muslims. The SSNP never shed its stridently anti-religious and radical secularism; in contrast, 'Aflaq acknowledged the Islamic spirit and tried to accommodate it. All these reasons contributed to the SSNP remaining a party of minorities, while the Ba'th attracted a fair number of Sunnis.

Pure Pan-Syrianism suffered from intellectual poverty. Pan-Arabism (whether radical or moderate) attracted many thinkers who developed a powerful and nuanced argument for the Arab nation; in contrast, pure Pan-Syrianism was promoted only by Antun Sa'ada and his idiosyncratic, if talented, band of followers. This lack of articulation goes far to account for the failure of Pan- Syrianism to be established as a reputable ideology and attract a large following.

One can go so far as to say that the anti-SSNP position was better articulated than the SSNP position. Note, for example, the case of Abu Khaldun Sati' al-Husri. Husri, perhaps the leading theoretician and exponent of Pan-Arabism, long took interest in the SSNP; he met with Sa'ada and even wrote a book about SSNP ideology. He disagreed with pure Pan-Syrianism, to be sure, but he took the SSNP seriously and argued with its respectfully. But the SSNP, reeling from its failed 1955 coup in Syria, provoked Husri and he responded in 1956 with a vicious refutation of the SSNP, dealing it a severe blow. Bassam Tibi explains this event's significance: "The massive attack of such an influential political writer as al-Husri on the SSNP, which had not yet gained a strong foothold, severely damaged its development. Husri's critique was used by all the Party's opponents."

The SSNP never succeeded in attracting many followers outside Lebanon and Syria; in contrast, the Ba'th won sizeable support in Iraq, Jordan, and other countries, all of which added to its strength.

On the tactical level, the Ba'th showed cunning and flexibility, joining with or dropping others (al-Hawrani, Nasser) as suited the moment. In contrast, the SSNP formed few alliances, remained isolated among enemies, and suffered constant persecution.

The Ba'th's greater agility was especially apparent in its showdown with the SSNP in 1955. In the course of its coup attempt, an SSNP member shot Lieutenant Colonel 'Adnan al-Maliki, a leading Ba'thist and one of the most powerful officers in the Syrian army. Maliki's death was a serious blow but Ba'th leaders made the most of the political opening it created. They mounted a show trial of the SSNP which placed all the party's activities-including its program and goals-under scrutiny. Following the trial, persecution of the SSNP began. It was made illegal (and remains so until the present); non-Ba'th officers joined Ba'thists in purging SSNP members from the government and the armed forces, where they numbered about 30 officers and 100 NCOs (that al- Hawrani, formerly of the SSNP, directed these efforts must have made them all the more galling); and the authorities tried to catch all SSNP members in Syria.

These steps had almost complete success; the SSNP was driven from Syrian political life and the balance between the two parties was permanently altered.

A Tool of Damascus

Though long-standing ideological rivals, the SSNP and Ba'th became bitter enemies only after the Maliki affair. It seemed certain that the hostility between the SSNP and the Ba'th would go on indefinitely, or at least until the former was crushed. During the Lebanese civil war of 1958, for instance, the Ba'th went after the SSNP with special venom. But their enmity did not continue; instead, the two parties underwent ideological and political transformations. In the process, the SSNP ended up an instrument of the Ba'th, while the Ba'th took on some of the ideology of the SSNP. This crossover led to the two becoming close if wary allies.

Spectacular failures suffered by both the Ba'th and SSNP in late 1961 sparked these changes. We have already seen how the SSNP's failed effort to overthrow the government of Lebanon in December led to its (public) repudiation of pure Pan-Syrianism and its refuge under the cover of Pan-Arabism. A generation later, that repudiation still stands.

The Ba'th experienced a more thorough transformation, changing inwardly as well as outwardly. In its case, it was the breakup of the United Arab Republic (UAR) in September 1961 that precipitated changes. Formed in 1958 as a total merger of the Syrian and Egyptian states, the UAR then quickly soured. But three and a half years elapsed before Syrian officers extricated their country from Cairo's grasp. Collapse of the UAR discredited the Syrian Ba'th Party's old dream of radical Pan-Arabism. (Branches of the Ba'th Party in other states, notably Iraq, were not affected in the same way.) The travails of union with Egypt disabused all those who assumed that the formation of a Pan-Arab union would be easy; further, eliminating borders between Arab states no longer looked so attractive. The UAR debacle also strengthened the sense of being a Syrian and the attachment to this identity. After the UAR experiment, many Syrian citizens who previously had scorned their polity as meaningless came to appreciate it.

Indeed, a new strand of thinking emerged in the Ba'th Party - Regionalism. Regionalists made Syria (and not the Arab nation) their primary field of attention. So intensely did they concentrate on Syria that Satic al-Husri, keeper of the Pan-Arabist flame, wrote disapprovingly about "the strange matter of Ba'thists taking up Syrianism. Michel 'Aflaq, the Ba'th ideologue, went so car as to accuse the Regionalists of pursuing a parochial nationalism (iqlimiyya) resembling that of the SSNP. As radical Pan-Arabism disappeared from the Ba'th program in Syria, giving way to pragmatic Pan-Syrianism, the party took on a whole new cast. For this reason, scholars have dubbed the post-1961 party the Neo-Ba'th. Further changes in government only confirmed the evolution away from Pan-Arabism. Bitar observed, with reason, that the 1966 coup "marked the end of Ba'thist politics in Syria." Michel 'Aflaq put the same sentiment more pungently: "I no longer recognize my party!"

Oddly, the events of late 1961 turned the SSNP and the Ba'th into mirror images of each other. The SSNP kept its real doctrines but adopted Pan- Arabism for cover; the Ba'th Party of Syria adopted a position congenial to the SSNP but purported to maintain its original ideology. The SSNP talked like the Ba'th, the Ba'th acted like the SSNP. There was, however, a consistency in this behavior; both parties found it advantageous to pursue Pan-Syrian goals under the cover of Pan-Arabist rhetoric. The failures of 1961 had the curious effect of compelling each party to adopt elements of the other's ideology. A former British ambassador to Syria and Lebanon, David Roberts, observes that "the Ba'th has parted company with the PPS and indeed banned it; but it has quietly absorbed its message." The crossover culminated when significant numbers of SSNP members joined the Ba'th With this, the Neo-Ba'th became almost indistinguishable from the SSNP.

The Syrian government's acceptance of pan-syrianism then changed relations between the SSNP and the Neo-Ba'th almost beyond recognition. Its shift toward Pan-Syrianism began in 1961 and culminated in 1974, four years after Hafez al-Asad came to power. Through a pragmatic and not a pure Pan- Syrianist (and so, potentially still a Pan-Arabist), Asad agreed on many essential matters of foreign policy with the SSNP. He sought to bring all four countries that constitute Greater Syria under the rule of Damascus; indeed, as earlier ambitions toward Egypt and other distant regions withered, this became a central objective of Syrian foreign policy. According to Laurent and Annie Chabry, the Asad government "uses the foil of Pan-Arabism to pursue a Pan- Syrian policy of the sort once promoted by the SSNP."

Mutual interests made the SSNP a client of the Syrian state and after decades of competition, the two sides became closely allied in Lebanon in 1976. In addition to a growing ideological compatibility, this may have had something to do with personal connections, for the Makhlufs, the family of Asad's wife Anisa, had a history of involvement with the SSNP. One of Anisa's relatives, 'Imad Muhammad Khayr Bey, was a senior SSNP official until his assassination in 1980. Rumor in Syria held that Anisa was sympathetic to the party and influenced Asad not just to cooperate with the SSNP, but also to look favorably on Greater Syria.

Not all elements in the SSNP accepted Syrian patronage, and this led to a series of schisms that left the party split into several factions: Maoist, Rightist (led by George 'Abd al-Masih), and pro-Syrian. In'am Ra'd led the last faction for some years; under pressure from Damascus, he was succeeded in July 1984 by 'Isam al-Mahayiri, the party's first Syrian-born and Muslim leader. Ra'd was docile enough to let himself be trotted out for foreign visitors (such as the Reverend Jesse Jackson when he visited Syria in January 1984); but Mahayiri, a lawyer and the scion of a prominent Damascene family, proved an even more willing agent. Mahayiri much understated the case when he observed that "our relations with the Syrian regime [and] the Ba'th Party... are good and are developing." In fact, Mahayiri went to Damascus for consultations and probably for direction. Indeed, Israeli officials reportedly believed that Mahayiri took orders directly from Asad, and the Israeli Defense Minister, Yitzhaq Rabin, publicly characterized the SSNP as "entirely under the control of Syrian intelligence."

With Syrian money and arms, the SSNP militia became a small but significant actor in the Lebanese civil war. According to Israeli intelligence, Syrian forces allowed the SSNP unusually free movement in Lebanon-a sign of the two sides' close ties. According to Hezbollah, the two even staged joint military activities. One estimate put SSNP strength in 1975 at 3,000 troops, a sizeable number in Lebanon; and a clear hierarchy and strict discipline increased its effectiveness. One on-the-spot observer, Harald Vocke, went so far as to call the SSNP militia "the strongest fighting unit" of the anti-government forces and, following al- Fath, the Christians' "most important opponent." This is probably an exaggeration, but the SSNP militia did gain in importance following the PLO's 1982 evacuation from Lebanon. It opened offices in Syrian-controlled territory in the Bekaa Valley and ruled a portion of Lebanese territory to the south of Tripoli.

Asad also let the SSNP use Syrian media to promote its Greater Syria message. The engagement of Shawqi Khayrallah as a Syrian publicist was a striking example of this. Khayrallqh had been an editor of the SSNP magazine in 1945 and he conceived of the 1961 coup in Lebanon; then he disappeared from view. In 1976, he began writing editorials for the state-run Syrian radio and newspapers promoting the concept of Greater Syria, and did not mince words. On one occasion he called for the integration of Lebanon "into a Levantine [Mashragi] Union, currently woven by Syria, Jordan, and [Palestine]." Khayrallah also argued that the return of the Palestinians to their homeland must be based on an understanding that "Palestine is Southern Syria."

In return for this backing, the SSNP performed a number of services. It helped the Syrian effort by providing a friendly base for Syrian troops in its home area east of Beirut. Asad relied on his SSNP allies to undertake especially difficult operations in Lebanon. For example, he deployed SSNP troops against the Iranian-backed Hezbollah in June 1986. To ensure a favorable outcome, Syrian troops took up nearby positions and intervened when the SSNP needed help. Syrian troops in Lebanon looked out for the interests of the SSNP; thus, five members of Hezbollah were arrested that same month on the charge of assassinating an SSNP official.

The party was also the first (and as of this writing, the only) Lebanese group to look beyond the Israeli presence in Lebanon and call for strikes within Israel proper. Calling Zionism a "racist movement which seeks to destroy us completely as a nation," the SSNP declared itself "in a sate of continuous war against Israel regardless of any possible Israeli withdrawals from Lebanon or the land of Palestine."

Most importantly, the SSNP engaged in key acts of terrorism. Under the aegis of Asad Khardan, the party's "Commissioner for Security," suicide attacks proliferated. Ehud Ya'ari (who calls the SSNP "the oldest terrorist organization in existence") sees the party as "Syria's most reliable instrument of terror, and it is employed for particularly sensitive and dangerous operations that are beyond the capabilities of the Palestinian terror groups headquartered in Damascus."

Thus, Habib al-Shartuni, the man arrested for killing President-Elect Bashir Gemayel in September 1982 was a member of the SSNP. The group that claimed to have bombed the U.S. Marine barracks in October 1983 proclaimed its support for Greater Syria, making it likely that the SSNP had some role in this blast. It claimed responsibility for eight of the eighteen suicide bombings directed against Israel in southern Lebanon between March and November 1985.

Pointing to the SSNP as "responsible for staging spectacular attacks and suicide actions," Israeli forces retaliated in August 1985 by destroying the SSNP headquarters in Shtaura. May Ilyas Mansur, an SSNP member, set off a bomb on a TWA airliner in early April 1986 that killed four passengers. The SSNP has also been tied to the attempt, just days laer, by Nizar al-Hindawi to place a bomb on an El Al plane. These attacks not only contributed to the Israeli decision to quit Lebanon, but they had an important role in Lebanese politics: by showing that the Syrian government could match the ferocity of Shi'i fundamentalist attacks on Israel, they added to Damascus's stature. The importance that Asad attached to suicide attacks was clear from the attention he paid them. He personally endorsed suicide efforts in a May 1985 speech.

I have believed in the greatness of martyrdom and the importance of self-sacrifice since my youth. My feeling and conviction was that the heavy burden on our people and nation ... could be removed and uprooted only through self-sacrifice and martyrdom. ... Such attacks can inflict heavy losses on the enemy. They guarantee results, in terms of scoring a direct hit, spreading terror among enemy ranks, raising people's morale, and enhancing citizens' awareness of the importance of the spirit of martyrdom. Thus, waves of popular martyrdom will follow successively and the enemy will not be able to endure them. ... I hope that my life will end only with martyrdom. ... My conviction in martyrdom is neither incidental nor temporary. The years have entrenched this conviction."

With such sponsorship at the top, a cult of the SSNP suicides was perhaps inevitable: Schools, streets, squares, and public institutions throughout Syria are named after the suicide bombers, and the country's most popular singer, Marcel Khalifa, has recently monopolized the top spot in the hit parade with his anthem to the suicides. Video cassettes of the bombers' "wills" are available at sidewalk kiosks, and sales are consistently brisk.

Increasingly-and consistent with SSNP ideology-some of the SSNP suicides came from Syria. When asked why he joined a Lebanese movement, one bomber answered, "Is there a difference between Lebanon and Syria?" Conversely, a sixteen-year-old Lebanese girl who attacked an Israeli convoy in April 1985 with a booby-trapped car, killing herself and two Israeli soldiers, previously had made a videotape in which she sent greetings to "all the strugglers in my nation, headed by the leader of the liberation and steadfastness march, Lt. General Hafiz al-Asad." She too saw Lebanon as part of Syria.

The SSNP also provided services for Syria's allies. A member of the party shot the top Libyan diplomat in Lebanon, 'Abd al-Qadir Ghuka, in June 1983. He later told police that the Syrian secret service hired him for the attack at the behest of al-Qadhdhafi, who thought Ghuka intended to defect. Libyan money increased substantially in 1986; Qadhdhafi apparently hoped to use the party as Asad did, to shield him from direct responsibility for terrorist activities. This alliance became public in October 1987, when the SSNP announced that 250 members had signed up to fight for at least six months in Qadhdhafi's war against Chad.

For the most part, SSNP members were delighted by the Syrian regime's turn to Pan-Syrianism; after decades of tension with Damascus, it finally found an ally there in a leader committed to Pan-Syrian ideology. The SSNP leadership praised "Syria's brotherly role and heavy sacrifice" and concluded that Asad genuinely aspired to a Greater Syrian union. One of its members told an interviewer: "We cannot forget that Mr. Hafiz al-Asad-His Excellency the President of Syria-has declared many times that Lebanon is a part of Syria, that Palestine is a part of Syria. And if we believe that, and we have to-he has given all signs of being serious-it means that his interest in Lebanon is very genuine. He is playing the game very cautiously and intelligently."

Conclusion

Its legacy of frustration does not invalidate the significance of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, which introduced a panoply of new ideas to the Middle East. These include the ideological party, complete political secularism, fascistic notions of leadership, and a dedication to pull down borders between states. The party drew in and influenced a generation of leaders in Lebanon and Syria. Its repeated challenges to the Lebanese state denigrated the prestige and status of the authorities. And its militia had a substantial role in the Lebanese civil war. Looking over a half century of turmoil, David Roberts notes that "the PPS has had a curiously pervasive influence through intrigue, murder and an ideology which rightly foresaw would be effective in the Levant."

In one sense, the SSNP in the 1980s became stronger than ever before. No longer did it have to hide and plot clandestine coups. Instead, it enjoyed the patronage of one of the most powerful Middle East states and found freedom to maneuver in Lebanon's anarchy. Syrian help has transformed the party from a moribund relic to a dynamic force. Ehud Ya'ari writes that "men who had been forgotten since the 1940s or 1950s have recently reappeared in the role of mentors, political mummies come back to life. Slogans that had long faded or peeled off walls have been restored with fresh paint, and the aura of action that surrounds the SSNP is once again attracting young people to the symbol of the red hurricane." The party also tapped new sources of members, including Shi'is and Druzes.

But the long-term implications of alliance with Syria appeared ominous for the SSNP; Asad's support had a steep price. He sought to bring the party under Damascus's control and make it a shell for Syrian agents and an instrument of Syrian policy. The potential danger is clear; by agreeing to work so closely with Syria's rulers, the party forfeited the strength that had made it an important force over the decades-its visionary politics and fierce independence. Asad's success in dictating terms restricted the SSNP's capacity for autonomous action. If money and arms from Damascus allowed the SSNP to flourish temporarily, absorption by a police state rendered its future bleak. Alliance with Damascus contained the likely seeds of the SSNP's demise.

Perhaps aware of this, the anti-Syrian wing of the SSNP attempted to depose 'Isam al-Mahayiri as party leader in January 1987. In a coup marked by SSNP factions shooting at each other at the party headquarters, Jubran Juraysh replaced Mahayiri and threatened to try him before the SSNP Higher Council.

The revolt seems to have been specifically provoked by a Syrian effort to use the SSNP to fight its many enemies in Lebanon-Hezbollah, the Druze, the Palestinians, and the Sunnis. But Mahayiri called on his Syrian patrons and reestablished his position in September 1987. Despite this limited reassertion of the party's independence, its influence appears to lie mostly in the past.

Radical Politics and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party :: Daniel Pipes

-

25-08-10, 15:08 #5AvampostoOspite

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Ultima modifica di Avamposto; 25-08-10 alle 15:09

-

25-08-10, 15:09 #6AvampostoOspite

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

-

25-08-10, 15:10 #7AvampostoOspite

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

-

25-08-10, 15:11 #8AvampostoOspite

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

-

25-08-10, 15:12 #9AvampostoOspite

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

-

25-08-10, 15:14 #10AvampostoOspite

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

Rif: Antoin Sa'ada e il Partito Nazionale Socialista Siriano (P.N.S.S.)

The Maronites are Syriac Syrians I maroniti sono siriaco siriani

by Antoun Saadeh da Antoun Saadeh